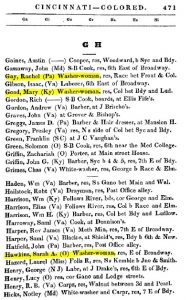

Walnut Hills had a long tradition of African American women taking in laundry. Calvin and Harriet Beecher Stowe engaged the services of an “Aunt Frankie” in the 1840s. A city directory from 1840, with a separate section for “Colored” with about 300 names listed no fewer than 16 with the occupation “washerwoman.” In Walnut Hills, the Cholera Epidemic of 1849 took the lives both of the Stowe’s eighteen-month-old son Charley and of Aunt Frankie. Modern understanding that the disease was spread through the feces of its victims helps us to understand how the lives of poor Blacks have always been endangered by their work in service industries. (Covid 19 is just the most recent stark example.)

Walnut Hills had a long tradition of African American women taking in laundry. Calvin and Harriet Beecher Stowe engaged the services of an “Aunt Frankie” in the 1840s. A city directory from 1840, with a separate section for “Colored” with about 300 names listed no fewer than 16 with the occupation “washerwoman.” In Walnut Hills, the Cholera Epidemic of 1849 took the lives both of the Stowe’s eighteen-month-old son Charley and of Aunt Frankie. Modern understanding that the disease was spread through the feces of its victims helps us to understand how the lives of poor Blacks have always been endangered by their work in service industries. (Covid 19 is just the most recent stark example.)

Our exploration of Lincoln Avenue through the 1870 and 1880 censuses showed that immediately after the Civil War, Black women (mostly recent immigrants from the South) continued the tradition of service as washerwomen. Fully a third of adult Black women in Walnut Hills in 1870 took in washing. By 1880 that fraction had increase to nearly half. It is difficult to know to what extent taking in washing supplemented the income of households with men and to what extent this occupation provided primary support for families – certainly, there were a number of female-headed households where washing was the sole means of support. Moreover, men’s work, often daily labor, could be precarious, with seasonal and weather disruptions. By the same token, sending the wash out to a washerwoman was the first step in most households toward middle-class status.

Laundry work was plentiful and necessary. Taking in laundry was the most basic, if demeaning and backbreaking work, a woman could do. Yet the ability to charge a fee, to earn a wage, changed everything for free and freed women. In addition to the dependable if modest income, it provided a sense of community. Laundresses set their own hours; they were able to work and raise their children; they played a significant financial role in their households, with or without men. They even provided little piecework jobs to others, generally sending men or older children to collect the dirty laundry and deliver the clean. This ancillary work could have provided additional tip income to the household.

There isn’t a great deal of evidence of how washing was organized in Cincinnati, let alone Walnut Hills. It was a week-long cycle that involved boiling and beating and drying on lines, as well as ironing and pressing. Clearly, customers needed a spare week’s supply of clothing to use the service. A wonderful book details the Black laundry business in Atlanta, the first city of the “New South.” There, the work was often communal, with women gathering to tend their fires for the initial hot wash, soaking and stirring the clothes for hours. This neighborly activity led African American women to organize “The Washing Society” in 1881. A labor movement, members went on strike for better wages, and incredibly they won! It is not clear whether the mostly southern immigrants in the Black community worked in concert as they established themselves in Walnut Hills during reconstruction.

It is clear that the Black community around Cincinnati had a political sense of solidarity with its washerwomen. In West Loveland there was an election for School Director in 1885. The population was about a third African American. “One of the candidates is N. B. Hawley, whom the colored element opposed because he started a steam laundry on the West Side, claiming that it is taking the bread from the washerwomen and their children’s mouths.” A Black man named Henry Estel joined the race in protest. Even the Commercial Gazette, usually a newspaper sympathetic to the Freedmen, closed with the snide comment “It is rumored that every colored woman will vote.” Women’s suffrage was of course thirty-five years in the future. Even though the reporter could casually dismiss the political power of African Americans, and especially the community’s women, he did have to recognize the beginnings of political organization.

Despite competing demographics and technologies, many Black women continued work as washerwomen through the censuses of the early twentieth century. As late as 1930, the seminal Black historian Carter G. Woodson could write an article titled “The Negro Washerwoman, a Vanishing Figure.” He noted that nationwide “the Census in 1890 reported 151,540 washerwomen, 281,227 in 1900, and 373,819 in 1910.” But that year was the peak. By the time of his article, he said “Through machinery and the division of labor the steam laundry has made the washing of clothes a well organized business with which the toiler over the wash tub cannot compete.”

Geoff Sutton

You may also be interested in Lincoln Avenue in 1870: What did women do all day?

Stay tuned for posts on the competition from Chinese Laundries, domestic Laundry Rooms, and Steam Laundries.