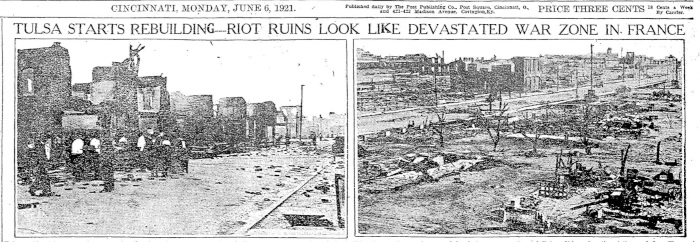

A hundred years ago, news arrived in Cincinnati of the overnight “Race Riot” in Tulsa, Oklahoma on May 31, and June 1, 1921. Everyone at the time knew that a race riot meant a white mob attacking a Black neighborhood. (Part of the horrible irony of the urban unrest of the 1960s is that the white press labelled them “race riots,” making a mockery of the term used for 150 years to describe white supremacist attacks.) Tulsa’s riot, now generally referred to as a “Race Massacre,” was perhaps the worst.[1] A few of the certain facts about Tulsa were that more than 1,200 houses, and all businesses, churches, schools and even a hospital in a 35-block area were burned to the ground with losses over $4 million[2]; more than 800 victims were treated in hospitals; more than 6,000 Black citizens were detained (as always, “for their own protection”) for up to a week. Since many bodies were burned with the buildings, and others may have been buried in mass graves, it is impossible to say exactly how many died, but responsible estimates range from about 100 to 300 Blacks, and perhaps a dozen whites.

The massacre is now well-documented; Tulsa is not our primary concern. Instead, this post examines the reaction in Cincinnati. First and foremost, Walnut Hills was to Cincinnati what the Greenwood neighborhood was purported to be in Tulsa – an enclave for wealthier and more professional Blacks. Walnut Hills to be sure had a range of wealth and income and included many extremely poor migrants from the South in 1921, but it was much better off than the contemporary populations in the old West End, or the East End around Lincoln School. The Tulsa riots, as covered by the press and history, offered a cautionary tale most clearly to our neighborhood in Cincinnati. Walnut Hills even had its own version of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street:” Burdette Avenue, racially integrated and home to several Black professionals, was sometimes known as “Burden of Debt.”

The massacre is now well-documented; Tulsa is not our primary concern. Instead, this post examines the reaction in Cincinnati. First and foremost, Walnut Hills was to Cincinnati what the Greenwood neighborhood was purported to be in Tulsa – an enclave for wealthier and more professional Blacks. Walnut Hills to be sure had a range of wealth and income and included many extremely poor migrants from the South in 1921, but it was much better off than the contemporary populations in the old West End, or the East End around Lincoln School. The Tulsa riots, as covered by the press and history, offered a cautionary tale most clearly to our neighborhood in Cincinnati. Walnut Hills even had its own version of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street:” Burdette Avenue, racially integrated and home to several Black professionals, was sometimes known as “Burden of Debt.”

Most of the attention in 1921 as now focused on the relatively well-off people in the segregated Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, the store owners and professionals and entrepreneurs and real estate brokers. (We have previously seen that the Black Walnut Hills entrepreneur Horace Sudduth had tried his hand at Oklahoma real estate in the first decade of the twentieth century before he returned to the Queen City area to be with his fiancée.) In fact, the single Black neighborhood in Tulsa – often called “Little Africa” in news reports – housed the poor and the destitute as well as the wealthy. The story of a bloodied “Black Wall Street” was perhaps even more frightening to the victims and the Race, and better emboldened white bullies and terrorists, than the truer understanding of an indiscriminate massacre of a Black ghetto.

The Union, Cincinnati’s Black newspaper published by Wendel Dabney, drew many lessons from the mayhem in Tulsa. Dabney emphatically decried the ghettoization of Black neighborhoods. He explicitly criticized the advice given by Booker T. Washington in 1913 to his National Business League in Oklahoma “to build up the sections which had been assigned to them.” Dabney continued, with chilling prescience,

The one great lesson to be learned from the horrible affair at Tulsa is that segregation and herding together are dangerous. The Jews have found it so in Europe, because it makes the work of the mobs easier. The fate of the Tulsa Colored people wipes out the theories of Washington.

The practice of redlining, refusing loans to potential Black buyers in white neighborhoods, was just beginning informally in the early 1920s. That full-fledged federal banking policy became official with the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934. Though finally outlawed in the late 1960s the practice continued.[3]

The Tulsa riots began, like most racial unrest at the time, with an allegation of a sexual assault by a Black man against a young white woman. The account was somewhere between exaggeration and complete fabrication – the woman never made any legal allegation. Dabney did not need to look far to find another example. On the page opposite the Booker T. Washington story, Dabney picked up a story from the New York News. When “an elevator operator was arrested charged with raping a white girl, … the daily papers all heralded the affair. … Under questioning …, the girl admitted in open court having willingly had improper relations … and the case was dismissed. Not one of the white papers carried an account of the dismissal.” Dabney remarked, “That’s what we are up against. Negro crimes are played with the loud pedal always.”

In the days after the riots, the white Cincinnati papers joined the rest of the country in condemning the “Negro agitators” responsible for the riots. In further foreshadowing of a long tradition of stories, this small number included a reputed “negro narcotic peddler as one of the principal leaders” while the rest were “nearly all dope users or jake drinkers with police records” – heavy condemnation indeed in the early years of prohibition. Yet in some of the very same articles, the white papers also praised white Tulsa for stepping up with reparations for the Black community. A white “Emergency Committee” announced as early as June 3 “we must rebuild these houses, see that these negroes receive their insurance and win their claims against the city and county.” The mainstream press reported on June 4 that “Homes for thousands of negroes made destitute will be built by Tulsa businessmen.”

In the days after the riots, the white Cincinnati papers joined the rest of the country in condemning the “Negro agitators” responsible for the riots. In further foreshadowing of a long tradition of stories, this small number included a reputed “negro narcotic peddler as one of the principal leaders” while the rest were “nearly all dope users or jake drinkers with police records” – heavy condemnation indeed in the early years of prohibition. Yet in some of the very same articles, the white papers also praised white Tulsa for stepping up with reparations for the Black community. A white “Emergency Committee” announced as early as June 3 “we must rebuild these houses, see that these negroes receive their insurance and win their claims against the city and county.” The mainstream press reported on June 4 that “Homes for thousands of negroes made destitute will be built by Tulsa businessmen.”

[1] The Tulsa Historical Society and museum web site has a detailed, balanced account with extensive documentation, at https://www.tulsahistory.org/exhibit/1921-tulsa-race-massacre/. The term “massacre” was used at the time of the destruction. See the Tulsa County Chapter of the American Red Cross Disaster Relief Committee, “Preface,” page 26 of the 102 page PDF https://www.tulsahistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/1984.002.060_RedCrossReport-sm.pdf . The official classification as a “riot” allowed insurance companies to refuse payment owing to a standard clause that used that term. See the Red Cross report of December 1921, p. 25, which is p 67 of the PDF.

[2] June 1, the day of the greatest destruction, set the value of property destroyed at $1.5 million, a figure repeated in all the early newspaper accounts. The report filed by the Red Cross totaled $4 million in insurance claims. A Red Cross account of “Resolutions” on July 31 1921 reported “millions of dolloars worth of property were stolen and burned.” Ibid., PDF p. 88. Many of the inhabitants of the neighborhood of course would not have been insured, so actual losses would have been higher. See the Red Cross “Supplement to the General Report, July 30, 1921” for the other statistics and many more.

[3] On redlining in Cincinnati, see https://walnuthillsstories.org/stories/redlining/