Black home buyers struggled against two great restrictions in the 1910s through the 1950s. The first was an increasingly hostile attitude in white neighborhoods toward prospective buyers: so-called restrictive covenants wrote racial prohibitions into property deeds. (The rapidly developing middle- and upper-class neighborhood of Hyde Park, just east of Walnut Hills, remains practically lily-white to this day as a legacy of the covenants of the first half of the twentieth century.) The second problem was the difficulty in obtaining financing. Walnut Hills avoided both of these bars, and Horace Sudduth played a crucial role in overcoming both. The previous post detailed his role in establishing the Industrial Savings and Loan Corporation. (A second Black building and loan, Major Lee Zeigler’s East End Investment & Loan Company, opened a branch a few blocks away in the former Devote Building at Chapel and Alms, in 1922.) Our next post will look at his work as an agent and broker in the single-family housing market. In this one we consider his role as a financier. We noted in the previous post that Sudduth took only a token dollar a year salary from the Industrial.

Black home buyers struggled against two great restrictions in the 1910s through the 1950s. The first was an increasingly hostile attitude in white neighborhoods toward prospective buyers: so-called restrictive covenants wrote racial prohibitions into property deeds. (The rapidly developing middle- and upper-class neighborhood of Hyde Park, just east of Walnut Hills, remains practically lily-white to this day as a legacy of the covenants of the first half of the twentieth century.) The second problem was the difficulty in obtaining financing. Walnut Hills avoided both of these bars, and Horace Sudduth played a crucial role in overcoming both. The previous post detailed his role in establishing the Industrial Savings and Loan Corporation. (A second Black building and loan, Major Lee Zeigler’s East End Investment & Loan Company, opened a branch a few blocks away in the former Devote Building at Chapel and Alms, in 1922.) Our next post will look at his work as an agent and broker in the single-family housing market. In this one we consider his role as a financier. We noted in the previous post that Sudduth took only a token dollar a year salary from the Industrial.

It is a century-old myth that lower-income home buyers (and especially Black buyers) are less likely to keep their mortgage payments up to date. Industrial Building and Loan was a financially sound institution. Following the stock market crash of 1929, the nation fell into the Great Depression; bank failures and mortgage delinquencies led the way. Yet both Sudduth’s Industrial Savings and Loan and Zeigler’s East End Investment & Loan remained solvent and emerged from the Depression as sound businesses.

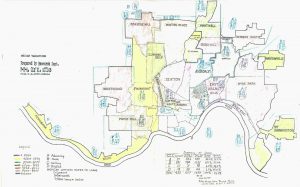

FDR’s New Deal included provisions to salvage the housing and mortgage markets. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) guaranteed many renegotiated loans. A sketched map from 1935 (apparently the only “redlining” document surviving for Cincinnati) tells the story. Loans in the “advancing” neighborhoods had a delinquency rate of just over 77% – indeed delinquencies topped 80% in Hyde Park. In “declining and blighted” neighborhoods the rate was a bit under 70% – to be sure, high by historical standards, but half again as many borrowers in distressed neighborhoods met their obligations compared to Hyde Park. Yet the HOLC did not target its support to neighborhoods like Walnut Hills with a lower percentage of loans in arrears; nor did it attempt to help low-income buyers.

Instead, the federal government officially recommended that loans should go to those “advancing” neighborhoods – tellingly, those with open lots still to develop. These were the areas with the highest home values. (It went unmentioned that they also had the lowest rates of repayment). In the more formal maps published for most cities, those area were printed in green, representing areas where guarantees would be a go. The poorer (though lower delinquency) neighborhoods, and explicitly those with more “Negros,” were “redlined;” in the more formal printed maps literally printed in red to indicate high risk. The Cincinnati sketch marks the Black neighborhood in Walnut Hills with a crosshatch pattern; the small Black neighborhood of West College Hill shows the same “redline” crosshatching. In short, in 1935 (as in the S & L crisis of the 1980s and the housing bubble of 2008), the federal government chose to bail out developers, bankers, and wealthy buyers despite the fact that low-income buyers were more likely to keep up their payments.

The main cause for bank failures during the depression was “runs” on banks. There were certainly many poorly managed institutions that just did not have enough assets to make good on their deposits. There were also perfectly solvent banks where depositors, fearing failure, rushed to withdraw their savings in order to protect their money, triggering short-term cash crunches that drove failures despite reasonable asset portfolios. The only protection against these irrational runs was the faith of the depositors that the bank was sufficiently well-managed to survive. It seems that Sudduth, and Zeigler, inspired that faith on the part of their depositors. That faith was upheld by the African American community that maintained its mortgage payments even through the depths of the depression.

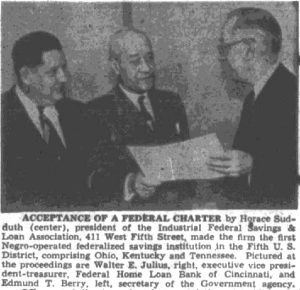

Throughout his long career, Sudduth continued to guide Industrial Building and Loan in the best interests of its members. In 1953 he brought the institution up to the standards required for a federal Savings and Loan charter – the first Black Savings and Loan to earn the credential in Ohio. This status allowed Industrial Federal to insure the savings of members up to $10,000 through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The institution took the new name “Industrial Federal Savings and Loan” to reflect its new status. After Sudduth’s death in 1957, Industrial Federal merged with Major Zeigler’s East End Investment & Loan to become the Major Federal Savings and Loan, a strong Black institution in Walnut Hills well into the 1980s.

Throughout his long career, Sudduth continued to guide Industrial Building and Loan in the best interests of its members. In 1953 he brought the institution up to the standards required for a federal Savings and Loan charter – the first Black Savings and Loan to earn the credential in Ohio. This status allowed Industrial Federal to insure the savings of members up to $10,000 through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The institution took the new name “Industrial Federal Savings and Loan” to reflect its new status. After Sudduth’s death in 1957, Industrial Federal merged with Major Zeigler’s East End Investment & Loan to become the Major Federal Savings and Loan, a strong Black institution in Walnut Hills well into the 1980s.

Geoff Sutton

For more, see Horace Sudduth: Businessman, Philanthropist, WH Resident

References:

The main recent book on Redlining is Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, W. W. Norton, New York, 2017. Rothstein and Mark Lopez made a 20-minute video “Segregated by Design,” available from the Zinn Education Project. Another excellent older video is “RACE – THE POWER OF AN ILLUSION: How the Racial Wealth Gap Was Created” by California Newsreel.

The image and caption about the federal charter are from “Business News,” Cincinnati Times Star, May 7, 1953 Page 38