We have seen that Andrew J. DeHart had joined the Grand Unified Order of Odd Fellows as a young teacher in Cincinnati in the mid-1870s. Upon his return to the Queen City in the late 1880s he reattached himself to the GUOOF and joined a related Black fraternal society, the United Brotherhood of Friendship. Like the Odd Fellows, the Brotherhood held regular meetings and collected dues, largely to pay the costs of members’ funerals. (It is worth pointing out that the United Brothers included a women’s organization called the Sisters of the Mysterious Ten.) DeHart quickly assumed a leadership role; for example, near the end of 1890 he travelled to Chicago to organize a UBF branch in the Windy City. DeHart joined the “National Grand Officers” of the organization the next year. In a meeting in Cincinnati, in August 1895, there was an appeal:

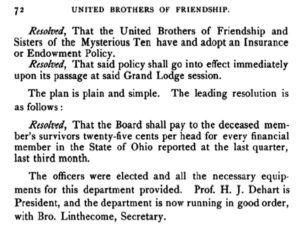

We have seen that Andrew J. DeHart had joined the Grand Unified Order of Odd Fellows as a young teacher in Cincinnati in the mid-1870s. Upon his return to the Queen City in the late 1880s he reattached himself to the GUOOF and joined a related Black fraternal society, the United Brotherhood of Friendship. Like the Odd Fellows, the Brotherhood held regular meetings and collected dues, largely to pay the costs of members’ funerals. (It is worth pointing out that the United Brothers included a women’s organization called the Sisters of the Mysterious Ten.) DeHart quickly assumed a leadership role; for example, near the end of 1890 he travelled to Chicago to organize a UBF branch in the Windy City. DeHart joined the “National Grand Officers” of the organization the next year. In a meeting in Cincinnati, in August 1895, there was an appeal:

To have so elaborate funerals as we usually do, and then afterwards visiting the home of the deceased, our eyes beholding sights most pitiable to behold, and our ears arrested with the touching cry, ‘Mamma, is there no bread?’ and the answer comes ‘No,’ from the survivors of one who has spent his life in the Order, and his interment was one of grandeur. Ah! had part of the money that was spent on his or her funeral been bequeathed to the family, it would have reflected honor and credit upon that brother or sister lodge, and also the Order of U. B. F.

The Brothers in Ohio determined to create a second insurance fund to make a payment to survivors of members, and in 1897 they elected DeHart president of the fund. The next year, he also served a term as President of the national UBF.

In 1890, as he was organizing this UBF life insurance fund, DeHart engaged in an even more business-like organization. After his return to Cincinnati in 1886 as the inheritor of several thousand dollars of family money, DeHart joined in the creation of the Garnet Loan and Building Association. The Garnet Company, founded in 1890, functioned as what would later be called a Savings and Loan, a type of bank that accepted investments from members and used the deposits to make loans to members to buy houses. At the organizational meeting DeHart was elected to the 15-member Board of Directors. This financial institution was duly registered with the State of Ohio; the directors put up a cash bond. DeHart (with retired Colored School Superintendent William Parham) joined the Appraising Committee. That is to say, A. J. DeHart was an active officer making financial assessments about where to grant loans.

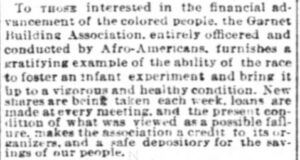

In 1890, as he was organizing this UBF life insurance fund, DeHart engaged in an even more business-like organization. After his return to Cincinnati in 1886 as the inheritor of several thousand dollars of family money, DeHart joined in the creation of the Garnet Loan and Building Association. The Garnet Company, founded in 1890, functioned as what would later be called a Savings and Loan, a type of bank that accepted investments from members and used the deposits to make loans to members to buy houses. At the organizational meeting DeHart was elected to the 15-member Board of Directors. This financial institution was duly registered with the State of Ohio; the directors put up a cash bond. DeHart (with retired Colored School Superintendent William Parham) joined the Appraising Committee. That is to say, A. J. DeHart was an active officer making financial assessments about where to grant loans.

The Cincinnati Enquirer, generally hostile to the African American community, published an effusive notice in late 1890, praising the bank, “entirely officered and conducted by Afro-Americans.” The Building and Loan constituted a Who’s Who of Black businessmen. Its leadership included many of the same men who had joined Cincinnati’s Civil Rights League. Early on it met in the Offices of undertaker William Porter, husband of Colored School teacher Ethelinda Davis Porter. (DeHart would hire their daughter Jennie Davis Porter as a teacher in the Walnut Hills Colored School — later Frederick Douglass School – in 1896.)

Garnet’s history also shows that leadership in the community was moving from the old West End downtown to Walnut Hills. In 1894,

The Garnet Building and Loan Company, the only financial institution here managed by colored men, with offices for three years downtown, has concluded to locate nearer the great body of its patrons, and will remove to Walnut Hills.

For several years it operated out of a small storefront on the northeast corner of Lincoln and Park Avenues. In about 1905 the DeHarts moved from their home at 1218 Chapel Street to Park Avenue, and the Garnett Loan and Building Company moved into their former house on Chapel. Garnet closed in 1906, so it isn’t clear whether the move to the former DeHart residence involved ongoing operations for the bank, or just cleanup in anticipation of dissolution. At any rate, it’s clear that DeHart’s relationship with Garnet Building and Loan was a close one.

Like most leaders in the African American community, DeHart also became an active member of the boards of several Black charities. He found a place as a trustee of the Colored Orphan’s Asylum in 1887, perhaps the most consistently supported Black Charity in the city, located on the border between Walnut Hills and Avondale. DeHart certainly devoted himself to the institution: it was a known quantity with a 40-year track record, and the board managed a well-established series of fetes and concerts for the benefit of its inmates.

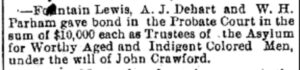

Considerably more challenging to begin with was the Crawford’s Old Men’s Home. It was endowed by a difficult white man who owed his safety during the Civil War to Blacks in the South, and who in 1880 left land, buildings and his estate to support Black elders, giving preference to those who had been enslaved. Crawford’s will had turned the management of his assets over to the wealthy Black coal dealer turned Walnut Hills real estate investor Robert Gordon. When Gordon died in 1884 leaving his own complicated estate to settle as well as Crawford’s, the process of creating the Old Men’s Home ground to a halt. It was not until early 1888 that the legal situation was sufficiently stable to restart the planning and development. At that time, DeHart again joined William Parham, one-time superintendent of the Colored Public Schools, and the wealthy Black barber Fountain Lewis as Trustees of Crawford’s Asylum for Worthy Aged and Indigent Colored Men; each of the three put up a $10,000 bond to the Probate Court. (There were very few mansions even in white Walnut Hills at the time worth as much as $30,000.)

Considerably more challenging to begin with was the Crawford’s Old Men’s Home. It was endowed by a difficult white man who owed his safety during the Civil War to Blacks in the South, and who in 1880 left land, buildings and his estate to support Black elders, giving preference to those who had been enslaved. Crawford’s will had turned the management of his assets over to the wealthy Black coal dealer turned Walnut Hills real estate investor Robert Gordon. When Gordon died in 1884 leaving his own complicated estate to settle as well as Crawford’s, the process of creating the Old Men’s Home ground to a halt. It was not until early 1888 that the legal situation was sufficiently stable to restart the planning and development. At that time, DeHart again joined William Parham, one-time superintendent of the Colored Public Schools, and the wealthy Black barber Fountain Lewis as Trustees of Crawford’s Asylum for Worthy Aged and Indigent Colored Men; each of the three put up a $10,000 bond to the Probate Court. (There were very few mansions even in white Walnut Hills at the time worth as much as $30,000.)

The financial aspects of DeHart’s complex story as a leader in the Black community in the late nineteenth century shows a clear history of generational and matrimonial wealth. Like many white residents of Cincinnati and of Walnut Hills, he used this wealth to support his community. He encouraged Blacks in the city, and especially in the neighborhood, to build similar wealth and financial stability. The Garnet Building and Loan provided both a stable, interest-bearing investment vehicle and a source of loans to acquire a house, always the major financial investment of families. The UBF insurance fund allowed surviving families of deceased Black members a modest income. The Colored Orphan Asylum and the Crawford’s Old Men’s home used community income and wealth to provide a minimal safety net at a time when government and white institutions failed Black Cincinnati.

Geoff Sutton