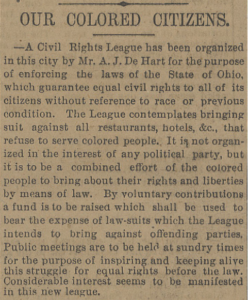

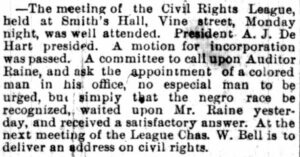

When Andrew J. DeHart returned to Cincinnati in 1885 with his wife, Jubilee Singer Jennie Jackson, the couple stepped into leadership roles in the Black community as well as in its school system. DeHart organized a “Civil Rights League” just months after his relocation to our city. The organizational meeting was reported on April 1, 1886; at a second meeting one week later, fifty Black members assembled and elected him president. Almost immediately, he raised $125 – nearly a month’s wages for even a professional like DeHart. In early 1887 the League took the legal precaution of incorporating.

When Andrew J. DeHart returned to Cincinnati in 1885 with his wife, Jubilee Singer Jennie Jackson, the couple stepped into leadership roles in the Black community as well as in its school system. DeHart organized a “Civil Rights League” just months after his relocation to our city. The organizational meeting was reported on April 1, 1886; at a second meeting one week later, fifty Black members assembled and elected him president. Almost immediately, he raised $125 – nearly a month’s wages for even a professional like DeHart. In early 1887 the League took the legal precaution of incorporating.

The League emerged in the early years of another controversial reform around hiring professional government employees, known as the civil service. Before reform, it was common for elected officials to divvy up government jobs among supporters and their constituencies; these “patronage” appointments were standard (often corrupt) fare in nineteenth century government. They had the disadvantages of hiring based on connections rather than qualifications, and of expiring whenever the responsible official’s party lost an election. The Black community to be sure had pursued such patronage appointments – based on the power of the Black vote – and with some success.

Candidates for jobs in the reformed civil service would take a test to establish their competence. Hires would be made from the pool of those who passed the test. Under this plan, those hired would become permanent government employees. To be sure, hiring managers still had discretion to choose among those who passed the test, but the bar was raised on qualifications, and continued employment under new administrations made the positions attractive to those pursuing long-term careers.

One of the Civil Rights League’s early projects sent a delegation to the Hamilton County Auditor in 1887, asking his office to hire a qualified Black candidate. Similar delegations in earlier years would have put forward one or more African American individuals as patronage hires. Yet the Civil Rights League asked for something different, within the scope and the spirit of the civil service reform movement. DeHart’s plea was for what a century later would later have been called affirmative action. Within the context of hiring based on qualifications, DeHart urged the auditor to choose a suitable African American candidate, without naming any individuals. The proposal was at least partly that the employer might just do the right thing – take notice of a qualitied Black rather than hire one of the white candidates who would otherwise be chosen by a prejudicial society. To be sure it was also still partly political – an exercise in softer political power by the Black community than the old patronage system, but implicitly tied to the significance of the Black vote. Whatever the motivation, the League’s ask met with some success.

One of the Civil Rights League’s early projects sent a delegation to the Hamilton County Auditor in 1887, asking his office to hire a qualified Black candidate. Similar delegations in earlier years would have put forward one or more African American individuals as patronage hires. Yet the Civil Rights League asked for something different, within the scope and the spirit of the civil service reform movement. DeHart’s plea was for what a century later would later have been called affirmative action. Within the context of hiring based on qualifications, DeHart urged the auditor to choose a suitable African American candidate, without naming any individuals. The proposal was at least partly that the employer might just do the right thing – take notice of a qualitied Black rather than hire one of the white candidates who would otherwise be chosen by a prejudicial society. To be sure it was also still partly political – an exercise in softer political power by the Black community than the old patronage system, but implicitly tied to the significance of the Black vote. Whatever the motivation, the League’s ask met with some success.

The Civil Rights League followed this plea for affirmative action with litigation against discriminatory practices in public accommodations. The laws were messy, and the suits ultimately futile. The Radical Republican Congress had passed a Civil Rights Act in 1875 that guaranteed equal access to “public accommodations” including trains, restaurants, hotels, and entertainment venues – enforcing the Reconstruction Era 14th Amendment right to “equal protection” under the law. An obstructionist US Supreme Court in 1883 declared the Civil Rights Act unconstitutional based on the perverse argument that white-owned businesses needed “equal protection” to decide who they would accept as customers. The court further ruled that only states could regulate Civil Rights of their citizens. At one stroke the court opened the wound of “States Rights” that festers to this day and granted a citizen’s right – freedom of association – to corporations.

To its credit, the Ohio Legislature attempted to mitigate the damage done by the Federal ruling. The US Supreme Court had left the door open to states to enact Civil Rights legislation. The state passed its own public accommodations law in 1884, providing equal access to eating establishments, transportation, and entertainment venues, allowing damages up to $100 in civil suits to victims of discrimination when access was denied on account of race. The penalty was certainly not enough to bankrupt most businesses, but it was high enough to string. It was this Ohio statute that DeHart’s Civil Rights League believed required a “thorough test.”

An African American lawyer from Springfield named John Hargo (who was an 1884 graduate of the Cincinnati College of Law) came to our city to visit the great Centennial Exposition in 1888. Two restaurants refused him service. The Civil Rights League took Hargo’s side in lawsuits seeking damages. The restauranteurs dragged out the litigation for more than a year. Hargo won in the initial trials, but he was only $25 in one case and a token $1 in the other. On appeal he was awarded the full $100 allowed by law in both cases, but the restaurants in turn appealed to the Ohio Supreme Court. The justices turned the US Supreme Court Civil Rights ruling on its head. The Federal decision had granted personhood to corporations and endowed then with freedom of association to exclude Blacks. The state Supreme Court ruled in favor of the restaurants, which were legal partnerships like corporations. The Ohio decision argued that individuals – in one case a waiter, and in the other case a single partner – had made the choice to refuse service to Hargo. Yet Hargo sued the businesses. It would not be fair, the justices argued, to penalize the business, and therefore all ownership partners, for the action of a single individual. So much for the federally declared personhood of corporations.

DeHart’s Civil Rights League launched a parallel campaign of naming and shaming discriminatory businesses. In the wake of the trials court’s initial toothless penalties against the restaurants, the League went to the organizers of the Exposition and asked that they survey businesses to determine whether – at least during the Exposition – they intended to discriminate against Black visitors. The request included a plea to publish in the official programs a list of those who intended defy the Ohio Civil Rights law, so Black visitors could avoid the embarrassment of being publicly ejected. Such naming, the Black community hoped, would also bring general disapproval on those businesses.

A similar tactic during the NAACP convention held in Cincinnati in 1946 – over half a century later – succeeded in causing some businesses to suspend their discriminatory policies during the convention, and others to close for duration of the convention. In the late 1880s, however, the efforts of the Civil Rights League only confirmed the beginning of unbridled Jim Crow segregation in our city.

Geoff Sutton