A. J. DeHart graduated from Cincinnati’s Gaines Colored High School in 1873. He went to work teaching in the “District” Colored elementary schools, one of the few occupations available to well-educated African Americans. During this first half-decade stint with Cincinnati’s Colored Public Schools, DeHart groomed himself in other ways for general leadership in the Black community.

A. J. DeHart graduated from Cincinnati’s Gaines Colored High School in 1873. He went to work teaching in the “District” Colored elementary schools, one of the few occupations available to well-educated African Americans. During this first half-decade stint with Cincinnati’s Colored Public Schools, DeHart groomed himself in other ways for general leadership in the Black community.Toward the end of 1875 he joined a Black learned society – the name “Scientific Society” it adopted took the term in a broader, nineteenth century sense. The organization boasted some three dozen members. Nearly all of them either taught in the public schools or had graduated from Gaines. Benjamin Arnett, pastor of Allen Temple AME church downtown (and earlier of Brown Chapel in Walnut Hills), hosted the organizational meeting and became president of the society. Arnett was an exception to the Colored School connection. DeHart served as corresponding secretary; his classmate Ernestine Clark, who by 1875 taught at their alma mater, won the honor of First Vice President.

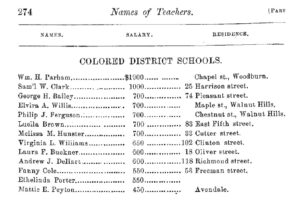

Apart from the organizational offices, the society chose “preceptors” or lead experts in nine fields. Arnett was charged with “Mental and Moral Philosophy” and DeHart with literature; fellow Gaines graduate Philip J. Ferguson took charge of music, as he did in the Colored Public Schools. Otherwise, the disciplines were what we would still call scientific. Peter Clark, principal of Gaines, took charge of “natural philosophy,” the contemporary name for physics and chemistry. (It is wonderful that this politically active and politically radical Black man was above all a science teacher.) The two women preceptors, DeHart’s fellow graduates in the Gaines class of 1873, studied zoology (Miss Clark) and paleontology (Miss Mattie E Peyton). Other Gaines teachers rounded out the expert fields of science: botany (Lewis D. Easton), minerology (William H. Parham), and taxidermy (G. H. Baily). This self-education society would have done a small, white college proud during Reconstruction. It is nothing short of amazing that it flourished in the Colored Public Schools of Cincinnati.

Nor was this DeHart’s only membership in a key Black organization. He continued to play for Peter Clark’s Black Vigilant Baseball team, holding down shortstop in 1875 and 1876 as the team ran up 160 wins without a single loss. Some of those victories came against white clubs.

Also in 1876, DeHart appeared as an incorporator, along with the Rev. Arnett and seven others, of “The African Company” in Covington, Kentucky. The vague notice stated that “the object of the company is to engage in trade and commercial transactions in Africa.” While the corporation hoped to raise $5 million with shares selling for $100 each, the shares could be paid in $10 installments, so it is unlikely that there was any substantial capital. A quick search on the company name produced no further information.

So-called “Secret Societies” like the International Order of Odd Fellows and the Masons provided important social and business contacts during the last third of the nineteenth century. By January 1877, DeHart took his place in the hierarchy. At the annual “memorial services held by colored Masons in Allen Temple … exercises were conducted by William H. Parham, Principal of the Public Schools in this city … Grand Senior Warden Sam’l W. Clark, Grand Junior Warden Lewis D. Easton; Grand Chaplain, Andrew J. DeHart” – all teachers in the Colored Public Schools. Black masonic lodges existed alongside white, although it does not seem any were integrated.

We have seen elsewhere that the large “International Order of Odd Fellows” offered a fraternal place, and an important commission, to the Italian immigrant Louis Rebisso in Walnut Hills. He was an immigrant, but he was white. Yet the IOOF closed its doors to African Americans. The community responded by soliciting a charter from Odd Fellows in England which lent the Black organization as much ancient credibility as the white IOOF. They founded the even more universally named Grand Unified Order of Odd Fellows. Histories record a few chapters on the east coast from the 1840s, but the order grew hugely after the Civil War. When the organization launched Cincinnati’s GUOOF Benjamin Lundy Lodge in 1876, the three names on the official Articles of Incorporation included that of A. J. DeHart.

Religion presented another locus of dignity and power in the Black community as well as in the white. DeHart engaged in the Church as well; he served as a Sunday School teacher at the large Union Baptist Church in downtown Cincinnati. It is difficult to know to what extent these “Sabbath Schools” in Black churches primarily offered religious instruction, to what extent they complemented the educational mission of the Colored Public Schools, and to what extent they offered academic work to children and adults who were unable to attend school, usually owing to obligations to support their families.

Religion presented another locus of dignity and power in the Black community as well as in the white. DeHart engaged in the Church as well; he served as a Sunday School teacher at the large Union Baptist Church in downtown Cincinnati. It is difficult to know to what extent these “Sabbath Schools” in Black churches primarily offered religious instruction, to what extent they complemented the educational mission of the Colored Public Schools, and to what extent they offered academic work to children and adults who were unable to attend school, usually owing to obligations to support their families.An account of the first Christmas program presented under DeHart’s leadership drew attention to practices borrowed from Gaines High School. Like the school exercises, the Christmas program at Union Baptist included music and “declamations” – recitations of famous speeches, poems, and essays. A report in the New National Era, a Washington weekly published by Frederick Douglass and his sons, carried the byline “DePugh.” This was the middle name, and the pen name, of Gaines teacher Louis D. Easton. His article noted that DeHart had graduated from Gaines and credited the young man with the excellence of the declamations by the Sunday-School scholars.

Easton also touted the fourteen-year-old accompanist Clara Skinner, whom Easton identified as a pupil of Cincinnatian Ella Sheppard “now with the [Fisk] Jubilee Singers in Europe.” Sheppard had herself been a child prodigy in Cincinnati and passed on her keyboard skills on both piano and organ. DeHart, too, enjoyed a reputation as a musician; in 1876 he would be featured in a duet, and a solo, in a fundraising concert for Union Baptist at the (primarily white) Melodeon Hall at Fourth and Walnut. Yet it was above all his skill with declamation that led him to a new career in the ministry.

– Geoff Sutton