We have been following the career of Andrew Johnson DeHart, an 1873 graduate of Cincinnati’s Gaines Colored High School, as he taught in the Colored District (elementary) Schools. DeHart also took his place in Cincinnati’s Black elite. In the years following the Hayes-Tilden election in 1876, when sometime Cincinnatian Rutherford B. Hayes agreed to remove Federal Troops from the South as the price for Tilden’s acquiescence in the contested presidential election, the South became increasingly hostile and dangerous for its Black citizens, and DeHart was at the forefront of relief efforts.

In 1877, A. J. DeHart served as assistant secretary to Cincinnati’s Homestead and Land Association. The purpose of the Association was to provide support for a Black “Exodus” from the South to more promising lands in the West. The wealthy retired Black coal merchant Robert Gordon in Walnut Hills took on the role of treasurer. George Washington Williams, at the time pastor of Union Baptist in Cincinnati, served as president. One possible destination for those fleeing the fury of the Ku Klux Klan and other white terrorists was eastern Kansas – a state with very cold winters advertised as in the “Southwest.”

Even while he taught in the Cincinnati Colored Schools, DeHart also took on an increasingly significant religious role. We have seen that he served as a Sabbath School teacher in Cincinnati’s large downtown Union Baptist Church. In October 1876, the ten-year-old Avondale First Baptist Church presented him with a license to preach. (The Church would later become Corinthian Baptist Church, still an active Black congregation today.)

Despite his promising place in Cincinnati’s Black community, beginning in 1878 DeHart indulged a religious and geographical wanderlust. He affiliated himself with the predominantly white Congregationalist denomination. (The name of the denomination can cause confusion; Protestant congregational churches with a small “c” are churches where the members of the church choose their own minister; Baptists were and are the largest congregational denomination.)

The Congregationalists (with a capital “C”) were originally New England Calvinists. (Harriett Beecher Stowe’s father Lyman Beecher had been a Congregationalist until he came to Cincinnati; he made the simple transition to Presbyterianism during his voyage to our city in the early 1830s.) Sheer demographics made the churches overwhelmingly white. Yet he denomination in New England had been staunch abolitionists in the decades before the Civil War. They sponsored the American Missionary Association (AMA), an often financially troubled organization that nonetheless founded Fisk, Berea, Hampton, and half a dozen other Reconstruction era Historically Black Colleges and Universities. DeHart would find himself at the head of several young Black Congregationalist churches (often referred to in the South as simply “Christian” Churches) in his ministerial career.

The Congregationalists (with a capital “C”) were originally New England Calvinists. (Harriett Beecher Stowe’s father Lyman Beecher had been a Congregationalist until he came to Cincinnati; he made the simple transition to Presbyterianism during his voyage to our city in the early 1830s.) Sheer demographics made the churches overwhelmingly white. Yet he denomination in New England had been staunch abolitionists in the decades before the Civil War. They sponsored the American Missionary Association (AMA), an often financially troubled organization that nonetheless founded Fisk, Berea, Hampton, and half a dozen other Reconstruction era Historically Black Colleges and Universities. DeHart would find himself at the head of several young Black Congregationalist churches (often referred to in the South as simply “Christian” Churches) in his ministerial career.During and after the Civil War, Congregationalists launched a vigorous project to create both educational institutions for the Freedmen and independent Black churches with Black clergy trained in the schools. (This model of parallel, segregated churches was already established in the Episcopal, Baptist and Methodist denominations, especially in the North.) In 1878 DeHart was ordained as minister to Mt. Zion Congregational Church in Cleveland, the first Black Congregationalist church anywhere, organized during the Civil War in 1864. (It remains a vital Black Church in Cleveland to this day.)

In 1879 or 1880, DeHart travelled from Cleveland to Topeka, Kansas. His departure for Kansas among people of the “Exodus” from the South makes sense, given his work in Cincinnati with the Homestead and Land Association. “Bleeding Kansas” territory had its own fierce battles on the eve of the Civil War to determine whether it would join the Union as a free or slave state. In January 1861, after Lincoln’s election but before his inauguration, a free Kansas entered the Union and moved its capitol to Topeka, the center of free-soil activity. The sequence of events is a little confusing, but DeHart served as the pastor of the Second Congregational Church of Topeka, presumably a congregation of Southern African Americans seeking a promised land in Kansas.

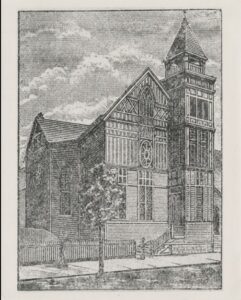

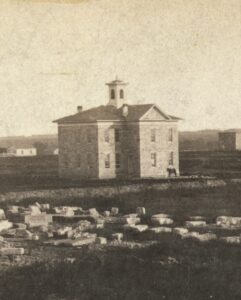

In 1879 or 1880, DeHart travelled from Cleveland to Topeka, Kansas. His departure for Kansas among people of the “Exodus” from the South makes sense, given his work in Cincinnati with the Homestead and Land Association. “Bleeding Kansas” territory had its own fierce battles on the eve of the Civil War to determine whether it would join the Union as a free or slave state. In January 1861, after Lincoln’s election but before his inauguration, a free Kansas entered the Union and moved its capitol to Topeka, the center of free-soil activity. The sequence of events is a little confusing, but DeHart served as the pastor of the Second Congregational Church of Topeka, presumably a congregation of Southern African Americans seeking a promised land in Kansas.The 1880 census listed DeHart as a student at the tiny AMA-sponsored Washburn College, founded in 1866. Like most AMA colleges, Washburn during the early years included a preparatory department larger than the college. It accepted men and women, boys and girls, including at least one Black student in its first preparatory class in 1866. It had a faculty composed of white college-educated Congregationalists from the North. Reports for 1880/81 included a note under the headline “The Appeal of the Exodus.” Apart from the college, Missionary Association had purchased a lot and constructed a building in Topeka that served as a night school for students unable to attend day classes. In addition, it housed a Sunday School “under the charge of Mr. A. J. DeHart, a young colored man from Washburn College, recently ordained by a council at Cleveland.” Elsewhere, the article remarked that the Sunday School had an average attendance of 170.

At 25 years of age, DeHart was the oldest in the census cluster of 22 students; the others ranged from 16 to 20, presumably enrolling in either the preparatory or college courses. DeHart was the only student of color in the group. It seems he earned a degree in Divinity; while Washburn was never a seminary, he was afterwards occasionally referred to as Dr. DeHart. At any rate, he solidified has connections with the Congregationalists and gained an important educational credential.

Like many others in the Black Exodus to Kansas, DeHart stayed only a few years.

– Geoff Sutton