(See also Women Doctors in Cincinnati and their Connections to Walnut Hills.)

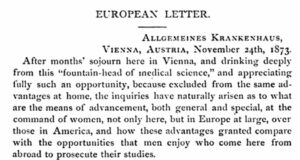

We have met Walnut Hills resident Dr. Elmira Howard as a Walnut Hills physician practicing in Cincinnati from 1870 through the mid-1890s. She had earned her MD at the New York Medical College for Women, receiving training comparable to that of most male medical school graduates in the US. In the summer of 1873, however, she departed for Europe to further her medical education. From our very German city, it is not surprising that Dr. Howard chose Vienna for a year’s advanced study. She sent a series of long letters to her fellow doctors in Cincinnati describing her findings. The letters all appeared in The Cincinnati Medical Advance, a journal for Homeopathic doctors, and at least one was reprinted in the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper.

Elmira Howard offered a telling insight into medical training for women in Vienna. While a few professors restricted their classes only to men, most freely admitted women and offered documents of completion of courses to all on an equal basis. That is to say, Dr. Howard enjoyed the same post-graduate training and credentials as her male American counterparts. She observed that this liberality with respect to gender made Vienna the “’Mecca’ where woman practitioners will come.” On the other hand, the medical school, the degree-granting institution, did not accept women, so the coeducational advantages allowed to foreigners (and, technically, to Viennese women) supplied no viable path to the profession for German women.

Most of the content of the Vienna letters touched on medical procedures and practice – not reading for the faint of heart. One recounted the treatment of gangrene in the Vienna hospital (a procedure now known as debridement – scraping away the dead tissue) and the chemicals used to prevent further infection, repeated again and again in cases of recurrence. Perhaps closer to the front lines of emerging scientific medicine, Dr. Young provided an account of a transfusion for a woman hemorrhaging after a miscarriage. The technique was developed in 1865, less than a decade before Dr. Howard’s study in Vienna. The patient received a direct transfer of blood from her sister; the lecturer described the suction cups, needles, tubes and valves required to ensure the transferred blood was nowhere exposed to the air which could produce fatal clots.

“Here one cannot lack, either, for opportunities of study, for, beside the University, which is connected with the hospital, and which holds its sessions nine months of the year, instead of four or five, as do our medical colleges at home – and which time, with us, constitutes a medical school year – we have also during the vacation, which extends from the 1st of July to the 1st of October, a series of private courses, by most able teachers, upon such branches and terms as are most enticing to earnest students.”

“With these [teachers] every student has the privilege of walking the wards daily, from 7 to 9 in the morning and from 4 to 6 in the afternoon, with the primartz or house physician in the different divisions, and here witnessing continually all the diseases ‘flesh is heir to,’ as well as so much of surgery that one begins almost to think these poor creatures were only made for surgeons to practice upon.”

The post-graduate year in Vienna put Elmira Howard into an elite class of doctors in Cincinnati. It also allowed her to mentor women who increasingly found their ways to medical schools and MDs in the US. Stay tuned for her work as a “preceptor” to the Black physician Consuelo Clark.

- Geoff Sutton

For more on Dr. Howard see https://walnuthillsstories.org/stories/elmira-young-howard-doctress-with-an-md-from-a-womens-medical-college/