The massive limestone walls of the Eden Park Reservoir represented only the first step in the construction of the new Water Works. They left two pockets in a dammed ravine: the upper basin at the base of what would become the dividing wall between the two compartments was fifty feet deep. The lower wall, as we have seen, soared 120 feet from its foundation. To create usable reservoirs, the engineers needed to fill the bottoms of the pockets inside the walls until they provided flat floors only 30 feet below the tops of the walls. The engineer Joseph Earnshaw decided to fill the pockets created by the reservoir walls with a mixture of waste limestone and shale, a material he referred to as “blue clay.” He reasoned that the clay would fill in any voids in the waste rock, providing a stable base for the concrete lining. Inside the reservoir his plan succeeded completely. Below the outer wall, however, the shale (without layers of solid limestone for support) was susceptible to clumping and sliding. The resulting “mudslides” below Eden Park have plagued the Queen City ever since, and periodically close Columbia Parkway, another ambitious public works project launched in the 1930’s.

The massive limestone walls of the Eden Park Reservoir represented only the first step in the construction of the new Water Works. They left two pockets in a dammed ravine: the upper basin at the base of what would become the dividing wall between the two compartments was fifty feet deep. The lower wall, as we have seen, soared 120 feet from its foundation. To create usable reservoirs, the engineers needed to fill the bottoms of the pockets inside the walls until they provided flat floors only 30 feet below the tops of the walls. The engineer Joseph Earnshaw decided to fill the pockets created by the reservoir walls with a mixture of waste limestone and shale, a material he referred to as “blue clay.” He reasoned that the clay would fill in any voids in the waste rock, providing a stable base for the concrete lining. Inside the reservoir his plan succeeded completely. Below the outer wall, however, the shale (without layers of solid limestone for support) was susceptible to clumping and sliding. The resulting “mudslides” below Eden Park have plagued the Queen City ever since, and periodically close Columbia Parkway, another ambitious public works project launched in the 1930’s.

The Eden Park Reservoir project, like so many large-scale efforts during Reconstruction, fell woefully behind schedule and over budget. Bold projections in 1866 forecast that the whole Reservoir would go into service by the end of the decade. Yet each year saw new delays and increasing urgency: The great Chicago fire of 1871, and another in Boston in 1872, brought home the importance of a huge, high-pressure supply of water for fire suppression in a modern city. News accounts in the summer of 1873 suggested the upper reservoir in Eden Park would be filled in September, but another year passed before work appeared to be finished. As if on cue, a fire broke out in a planing mill on Hunt Street (now Reading Road) just weeks before the first attempt to fill the reservoir in late 1874, causing $55,000 damage to several buildings. It was not until December 1874 that water finally found its way into the reservoir.

Immediately, the lining leaked. The national press picked up the story, with remarks like “The Cincinnati Reservoir will not hold water, and they talk of turning it into a magnificent music hall” and “The new reservoir at Cincinnati refuses to hold water; but the inhabitants are reconciled. They have long since learned to drink something else.”

Accusations came fast and furious. Some blamed the innovative use of blue clay used in the fill under the reservoir liners. Others suggested defective sewer lines underneath the foundations caused the leaks. Others blamed sloppy installation of the “effluent” pipe that would carry water from the reservoir to consumers. Accusations were leveled that the cement used to construct the liner had been rejected by a railroad company in Louisville before it was shipped to Cincinnati. (The Water Works Engineer Theodore R. Scowden, during work on the canal at Louisville during the Civil War, had established a cement plant there with a couple of partners; it’s not clear whether this influenced the order.) Further claims argued that the dividing wall between the upper and lower reservoirs leaked at the courses where work had been stopped for the winter each year, weakening the concrete at those points in the walls. Whatever the cause, the Water Works found itself with delicate situation. The pipes to and from the works were full of water, but the leaks prevented further pumping. Wintry weather threatened to freeze the still water and crack to pipes. Nonetheless the reservoir needed to be drained in order to trace the leaks.

It’s difficult to determine just what the fundamental problem or problems may have been. The work resumed on the drained upper reservoir in the spring of 1875. There were certainly some spots detected where the concrete liner was just leaky sand, although many places were appropriately solid. Inspection and repairs corrected difficulties real or speculative around the effluent pipe and in the sewers. The new water works went in to operation that year.

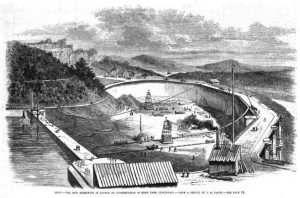

The illustration from Frank Leslie’s newspaper in 1878 shows the upper reservoir to the left full and operational, with work finishing up on the concreting of the lower reservoir.

References:

For general references, see the first article in this series, Construction during Reconstruction: Eden Park Reservoir Walls

On the blue clay controversy and defective cement, see The Cincinnati Enquirer (Cincinnati, Ohio), 24 Dec 1974, Page 4; 28 Dec 1874, Page 8; 22 Jan 1875, Page 7; 29 Jan 1875, Page 8; 06 May 1875, Page 4; The Cincinnati Daily Star (Cincinnati, Ohio), 03 Jul 1875, Page 1.

On Scowden and his cement plant, see Cincinnati Past and Present, Photographically Illustrated by James Landy (Cincinnati, 1872), pp. 373-377.

The illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper appeared 28 Sep, 1878, p. 61; the accompanying story appeared on p. 62.

For the quotes from other cities, see The Pittsburgh Daily Commercial (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) 18 May 1875, Page 2; Green Bay Press-Gazette (Green Bay, Wisconsin), 24 May 1875, Page 2; Williamsport Sun-Gazette (Williamsport, Pennsylvania), 25 May 1875, Page 2