We have seen that many Black women, and a few whites, worked as washerwomen in Walnut Hills from the 1870s through the early decades of the twentieth century. As with many forms of difficult physical labor, new technologies offered more efficient methods. Steam power was applied to laundry: The steam engine drove large industrial washing machines, and the boilers served to heat the water for the first soak, and to warm the drying rooms.

Walnut Hills, like the rest of Cincinnati, joined in this steam revolution. In 1882, a 40-year-old white mother of five, Sophia Beyer, opened the Walnut Hills Steam Laundry in the home she shared with her husband, a letter carrier. They lived on what is now Foraker Avenue at Park Avenue. This location was a block east of the Beecher-Stowe house which stands to this day at Foraker and Gilbert; the site of the Bayer home and the laundry on the north side of Foraker was cleared a century later to make way for Martin Luther King Drive.

The earliest years of the business leave their traces only in city directories, but it is striking that Mrs. Bayer’s name always appeared first in the business listings. Equally remarkable at the time, she was always identified with her own name or initials; she was Mrs. S. C. Bayer rather than Mrs. Charles Beyer. A steam engine, a commercial laundry machine and a drying room represented a considerable investment. We have seen that houses on Lincoln and Foraker typically sold for something like $600. Around the time Mrs. Bayer opened her business, a steam laundry in Mt. Auburn burned to the ground; the insurance loss was set at $1,000. Another laundry in nearby Hamilton, Ohio, was offered for sale at $3,000. This was no sideline for a local housewife.

Mrs. Bayer initially opened the business in partnership with Robert Chapple; perhaps she had his help with the capital outlay. Chapple briefly moved into the multi-generational Bayer household as he helped operate the business. By 1885 he returned to his family’s home and to their Walnut Hills boot business. There is no suggestion that Mr. Bayer had any involvement in the laundry in the early years. He lost his postal job, apparently owing to a failure of political patronage, in the late 1880s. For a few years, the city directory listed his occupation as the manager of the Walnut Hills Steam Laundry, although he may have managed nothing more than his pride. Mrs. Bayer was still recorded as the proprietor throughout. Mr. Bayer was reinstated as a letter carrier by orders from Washington in 1899; from 1900, the directory made no further reference to his involvement with the laundry.

Mrs. Bayer initially opened the business in partnership with Robert Chapple; perhaps she had his help with the capital outlay. Chapple briefly moved into the multi-generational Bayer household as he helped operate the business. By 1885 he returned to his family’s home and to their Walnut Hills boot business. There is no suggestion that Mr. Bayer had any involvement in the laundry in the early years. He lost his postal job, apparently owing to a failure of political patronage, in the late 1880s. For a few years, the city directory listed his occupation as the manager of the Walnut Hills Steam Laundry, although he may have managed nothing more than his pride. Mrs. Bayer was still recorded as the proprietor throughout. Mr. Bayer was reinstated as a letter carrier by orders from Washington in 1899; from 1900, the directory made no further reference to his involvement with the laundry.

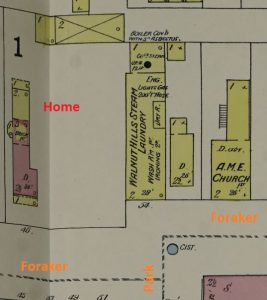

Listed addresses and the famous “jogs” in Walnut Hills streets make it difficult to figure out just when the steam laundry got its own building, next door to the Bayer house. An 1891 map shows the residence on what was then called Walnut (now Foraker), just west of Park. The laundry was next door, opposite Park at the T-intersection. The building to the east of the cleaning plant was an African Methodist Episcopal Church. Like the nearby blocks, the Bayer’s was racially integrated; from 1870 through 1900 all surviving census forms show one or another African American washerwoman just one or two doors away from the Beyers. We cannot know from the forms whether any of these Black neighbors worked for Sophia Bayer.

We can see, using the Walnut Hills Steam Laundry as example, the increasing scale and complexity of the business. By the late 1880s Mrs. Bayer was listed as the proprietress of the laundry; son Charles Jr. – more often referred to as Charlie – clerked in the shop, and his brother Albert was a driver for pickup and delivery. There are a few references to other employees, but no detailed records. The commercial laundry business was rapidly consolidating, and proprietor-operated laundries had trouble competing with larger chains. Fifty of the smaller businesses fought back by marketing themselves as a consortium using a common laundry slip they published in newspapers in the early 1890s. The Walnut Hills Steam Laundry was prominent among them, with a display ad in the list.

Nor was Mrs. Bayer the only woman in Cincinnati to launch a successful steam laundry. A Mrs. L. Varney listed herself in the laundry business beginning in the 1872 Williams Directory, and by 1875 she was the proprietress of the Home Steam Laundry on Race Street downtown. The business moved into the Emery Arcade and at least in terms of advertising and press was a leading competitor in the business in the late 19th century.

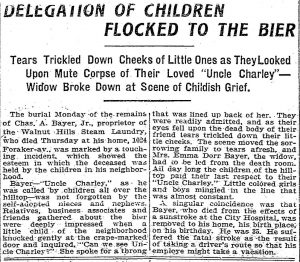

Sophia Beyer seems to have largely withdrawn from the business at about age 60. In 1903, the business passed to “Bayer Brothers,” sons Charlie and Albert, who were by that time in their early 30s. The whole family, including the adult sons, moved to a house in Norwood, retaining the laundry on Foraker. But the family business came to an abrupt and sad ending. You may need to click on the image to read the full story on the demise of the son “Uncle Charley,” mourned by Walnut Hills children Black and white, as it was covered in the Cincinnati Post. He died of sunstroke of an August day in 1904, kindly covering a delivery route for a vacationing driver.

Charlie’s sister Pearl was never listed as a part of the laundry business. Yet it was Sophie and Pearle who sold the business and the house next door to a William C. Lapham – provoking a lawsuit from Charles Sr. for fraud in the transfer of the house to his daughter. The next year Mr. Bayer, still a letter carrier, moved to Stanton Avenue, back in Walnut Hills. He took up residence with two elderly sisters, Christine and Dorothea Bayer, both teachers in the Cincinnati Public Schools.

In 1910 Lapham expanded the steam laundry on Foraker to more than twice its original size; the new construction also included an on-site restaurant for employees and “a restroom for girls,” as well as a new stable in the back. The modern brick building continued as a steam laundry until 1967, when it was destroyed by riots in south Avondale and Walnut Hills. The technology of the steam laundry continued long after it contributed to the demise of the Black washerwoman during reconstruction.

Geoff Sutton