This post about Chinese Laundrymen in Cincinnati a hundred and fifty years ago and the abuse they endured has suddenly become very topical. Hate crimes in Atlanta resulting in the deaths of six Asian Americans, as well as threats and harassment reported in Cincinnati, brings the question of “John Chinamen” – a close relative to Jim Crow – to the immediate present. Originally planned as the last in a series about African American washerwomen in Walnut Hills during the decades after the Civil War, this research also stands as a stark reminder of another nineteenth-century campaign of intimidation and suppression against a different “other.”

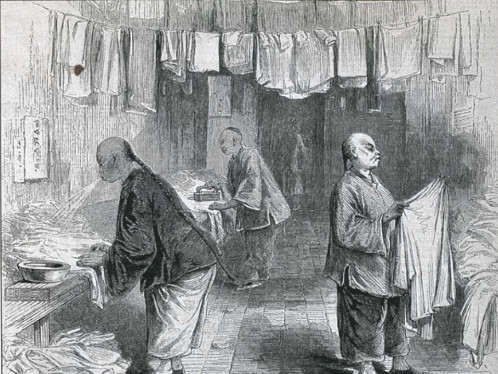

This post about Chinese Laundrymen in Cincinnati a hundred and fifty years ago and the abuse they endured has suddenly become very topical. Hate crimes in Atlanta resulting in the deaths of six Asian Americans, as well as threats and harassment reported in Cincinnati, brings the question of “John Chinamen” – a close relative to Jim Crow – to the immediate present. Originally planned as the last in a series about African American washerwomen in Walnut Hills during the decades after the Civil War, this research also stands as a stark reminder of another nineteenth-century campaign of intimidation and suppression against a different “other.”The last several posts have considered laundry work and methods in Walnut Hills in the 1870s and 1880s – Black washerwomen, mostly from the South, “took in laundry” from the 1870s, and continued to do so through the end of the century. Their work was challenged on the one hand by large commercial laundries powered by steam engines and their boilers, and on the other by more modest metal washtubs and drying closets in the basements of wealthy middle-class homes. Beginning in the 1870s, however, Black women faced further competition from Chinese Laundries. These establishments saw men engaging in the sort of washing by hand usually practiced by Black women.

How did these laundrymen get to Cincinnati? A relatively small number of Chinese men had arrived with the “Forty-niners” in the California Goldrush. The great transcontinental railroad craze after the Civil War required huge numbers of laborers. Chinese workers were generally given free passage to California (officially or unofficially to be repaid from their wages) and promised free passage home. Blasting tunnels and filling valleys in the Rockies required risk on a much larger scale than that of antebellum Irish labor in the East documented in story and song. Yet when the work in the West was done, the laborers, derided as “Coolies,” were largely set adrift without the promised return tickets.

It is worth noting that in China, like the US, laundering was seen as women’s work and generally happened at home. The Chinese railroad crews, isolated on the rail lines, of course managed their own laundry and cooking. The hugely male culture of the wild west meant that very few women were available to take jobs as domestic servants. Wealthy white Californians hired desperate Asian immigrants to fill these positions as cooks, “house boys” and launderers.

Some Chinese construction crews, and more individuals, found their way east. In West Virginia coal country Chinese labor contracts were considered, but it was calculated that Black Prison labor was even cheaper than Chinese. There are at least hints that Chinese crews worked on the Cincinnati Southern Railroad, and clear documentation that they worked on the Southern connection from Chattanooga to Birmingham. Yet more Chinese laborers travelled the country to find whatever employment they could, despite great prejudice against them. Seeking work and willing to do hard labor for low wages, Chinese men (like migrating African American women from the South) began to take in washing.

In the 1870s, a handful of Chinese men opened laundries in Cincinnati; by 1880, the business listings in the city directory included a full dozen Chinese names among the laundries. The few accounts of their work in Cincinnati are generally tinged with terrible racism toward these most recent “others”. Even relatively sympathetic reports made fun of Chinese names – one man named Hung was said to have been named after what he did to dry laundry. Just as we have seen that African American Pullman Porters were all called “George” after the owner of the company, so the laundrymen were all called “John Chinaman” or simply “John”.

In the 1870s, a handful of Chinese men opened laundries in Cincinnati; by 1880, the business listings in the city directory included a full dozen Chinese names among the laundries. The few accounts of their work in Cincinnati are generally tinged with terrible racism toward these most recent “others”. Even relatively sympathetic reports made fun of Chinese names – one man named Hung was said to have been named after what he did to dry laundry. Just as we have seen that African American Pullman Porters were all called “George” after the owner of the company, so the laundrymen were all called “John Chinaman” or simply “John”.This entrepreneurial spurt was cut short, however, by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. The federal legislation effectively ended Chinese immigration and encouraged the expulsion and even the extinction of most of the immigrants who had built the transcontinental railway. The railroad recruiters had restricted their efforts to young men. In 1865 the federal Page Act prohibited the immigration of women for “immoral purposes.” It was enforced always and only in the case of Chinese women – who were assumed to be prostitutes. In pseudo-scientific support for this law, it was falsely claimed that sexually transmitted diseases circulated in the Asian community but caused no symptoms in Asians. These diseases, the fearmongers contended, were fatal to white men.

Cincinnati did its part in restricting the growth of Chinese Laundries. In an 1886 laundrymen’s national convention here, two commercial washing machine vendors were “referred” for discipline because they sold machines on credit, and provided training, to Chinese laundries. That practice, apparently, came to an end. Nonetheless, the existing Chinese laundries mostly remained in business through the later 1880s. Only in the last decade of the nineteenth did the number begin to dwindle, although it is quite possible that these laundries simply took more generic or Americanized names. Indeed, in Walnut Hills alone there were three “Chinese Laundries” listed in 1949.

– Geoff Sutton

References:

The image of the Chinese Laundry is well circulated on the internet, usually dated 1881. I have not found the original source.

“Sixth Street is improving.“ Cincinnati Daily Star, July 29, 1875 Page 2

“Chinese Cheap Labor,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 6 1873, Page 4

“Wanted, people to send their clothes to the new Chinese Laundry,” Cincinnati Commercial, August 28, 1873 Page 3

See the full front page spread in Cincinnati Commercial Newspaper Archives September 13, 1869 Page 1 for and introduction to “The Chinese Question.”