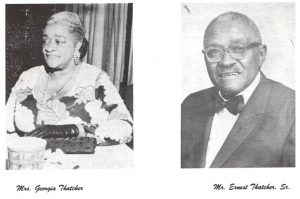

Ernest and Georgia Thatcher came to Cincinnati in 1929, a young African American couple from Kentucky hoping to make a better life together. His construction boss, a white man, agreed to help the Thatchers start a business in 1933; he paid their first few month’s rent on a storefront at 1015 Lincoln Avenue, and lent them $200. “Greatest gift I ever got.” The store always specialized in fresh fish and poultry, although over the years it featured other items in demand in the neighborhood, and continued in business in the same block for more than sixty years.

Ernest and Georgia Thatcher came to Cincinnati in 1929, a young African American couple from Kentucky hoping to make a better life together. His construction boss, a white man, agreed to help the Thatchers start a business in 1933; he paid their first few month’s rent on a storefront at 1015 Lincoln Avenue, and lent them $200. “Greatest gift I ever got.” The store always specialized in fresh fish and poultry, although over the years it featured other items in demand in the neighborhood, and continued in business in the same block for more than sixty years.

Early Years

In the early years, during the depression, the Thatchers handled chicken and at Thanksgiving and Christmas turkey – their listing in the city’s business directory was always “Retail Poultry.” But they also carried wild game like geese, pheasants and even turtles – foods familiar in the community of recent African American migrants from the South but not generally available in Cincinnati. The couple kept live poultry behind the store, and killed, cleaned and dressed what they sold. The children were kept busy cleaning the coops. The couple also worked hard to serve the Black elite in the neighborhood, including the teachers at nearby Fredrick Douglass school. (They even purchased a house across the street at 1008 Lincoln from the teacher Clara Willis in the late ‘40’s.) In the ‘30’s and ‘40’s, larger groceries didn’t carry fish, at least in Black neighborhoods, so the store catered to “high echelon” Walnut Hills customers as well. If the seafood stock ran low, they would send one of the children on a bicycle to the downtown wholesalers to replenish.

By the late ‘60’s the Thatchers (who managed to get occasional good coverage in the mainstream white press) supplemented their fish business with “a sort of pony keg with groceries” and took on their daughter Martha in the business. They continued to carry chicken, although Ernest was disappointed that he could no longer dress the poultry himself: “There are only a few small places left that are still dressing chickens. They eventually squeeze all of us out. Chicken was never my big seller, but just the idea of them pushing you around. Soon they’ll be telling you, you can’t sell fish.” The fish business continued strong, although he noted that “since the riots some of his white trade has fallen off.” At that time, Georgia Thatcher suggested it might time for the founders to retire. Her husband died at age 72 in 1974; their son Ernest Jr. joined the business.

Later Years

Later Years

In 1987, an upbeat Black business report in the Enquirer reported on Thatcher’s Fish Market, by that time in a larger store at 1008 Lincoln. Georgia Thatcher, age 77, was still at it every day handling phone orders and setting a close-knit family tone. Her son Ernest Jr. had retired; the heavier operations were managed by her daughter Martha, and Martha’s son Nadir Rasheed, a Black Muslim. Rasheed had graduated from the University of Cincinnati with a degree in philosophy, but in 1984 he decided to join the family business. Rasheed’s school-age son, a Douglass student, was around the store. Despite competition from supermarkets, strong roots in the neighborhood continued to bring in customers.

Another Enquirer profile in 1993 cast the situation in darker light. Martha had assumed ownership where her mother died in 1988, and ran the store in partnership with a nephew, George Thatcher. The text of the article quoted Martha speculating about advertising on Black radio, and expressing concerns that “Blacks say blacks should support black businesses, but they often don’t.” The article also identifies another, perhaps more significant problem: “Martha Thatcher … hopes that when the city reopens the eastern end of Lincoln Avenue in Walnut Hill’s black business district this summer, new customers might stop as they drive by the store. That portion of Lincoln Avenue was closed in the 1980s when Martin Luther King Drive was altered.”

Realistically, MLK replaced Lincoln as the only through street between Reading Road and Woodburn. The current Google map shows the Thatcher’s block as mostly vacant lots, with a small string of vacant storefronts – part of a three-block isolated backwater between Gilbert Avenue and MLK.