On the railroads, as on the steamboats, Black men would come to serve important roles in passenger service. Palace cars, first class accommodations owned by the Pullman company and leased to all the major railroads, served as a standard for luxury and service that rivaled the great hotels from the 1870s through the 1920s. Early descriptions of the Pullman cars frequently compared them to the cabins and staterooms on the grand riverboats. Like the steamboat porters in the 1860s and ‘70s we considered in the previous post, Pullman Porters were responsible for passenger comfort and amenities on board the trains. And even more uniformly than the cabin crews on the rivers, the Pullman Porters were all African American from the founding of the company in 1867 for nearly a century.

On the railroads, as on the steamboats, Black men would come to serve important roles in passenger service. Palace cars, first class accommodations owned by the Pullman company and leased to all the major railroads, served as a standard for luxury and service that rivaled the great hotels from the 1870s through the 1920s. Early descriptions of the Pullman cars frequently compared them to the cabins and staterooms on the grand riverboats. Like the steamboat porters in the 1860s and ‘70s we considered in the previous post, Pullman Porters were responsible for passenger comfort and amenities on board the trains. And even more uniformly than the cabin crews on the rivers, the Pullman Porters were all African American from the founding of the company in 1867 for nearly a century.

The company’s passengers, by law in the South and custom in the North, were nearly all white. In 1892, Homer Plessy, an “octroon” with seven white great-grandparents and one Black, entered a Pullman coach for which he held a ticket. He was removed for violating Louisiana’s 1890 “Separate Car Act,” The 1896 Supreme Court Plessy vs. Ferguson case that ruled state laws requiring segregated accommodations were constitutional. As with so much of the history of the nineteenth century, the Pullman Company collides uncomfortably with race.

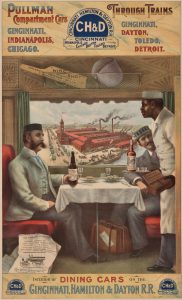

The image in this 1894 poster advertised the Pullman service. The art is sufficiently striking that it’s about the only nineteenth century image we find in brief histories of the Pullman Company. As it turns out, the ad also features our region, our city, and even our neighborhood of Walnut Hills. At first glance we see that the Pullman Compartment Cars were touted as an available service on the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad. The image includes more than half a dozen products from Cincinnati and nearby cities – an early example of product placement in of all things an advertisement. The newspaper on the floor is the Cincinnati Times-Star, the political organ of the Taft family. With literal as well as figurative wheels within wheels, the paper advertises Cincinnati’s Cook Carriage Company. Indeed, the poster itself was a Queen City product: small print in the lower right corner declared it was “Copyrighted in 1894 by the Strobridge Lith. Co Cin, O.” The Baker’s Paddle in the convenient rack above the window is from the “Wing Shot” oriental powder mills, also of the Cincinnati.

The image in this 1894 poster advertised the Pullman service. The art is sufficiently striking that it’s about the only nineteenth century image we find in brief histories of the Pullman Company. As it turns out, the ad also features our region, our city, and even our neighborhood of Walnut Hills. At first glance we see that the Pullman Compartment Cars were touted as an available service on the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad. The image includes more than half a dozen products from Cincinnati and nearby cities – an early example of product placement in of all things an advertisement. The newspaper on the floor is the Cincinnati Times-Star, the political organ of the Taft family. With literal as well as figurative wheels within wheels, the paper advertises Cincinnati’s Cook Carriage Company. Indeed, the poster itself was a Queen City product: small print in the lower right corner declared it was “Copyrighted in 1894 by the Strobridge Lith. Co Cin, O.” The Baker’s Paddle in the convenient rack above the window is from the “Wing Shot” oriental powder mills, also of the Cincinnati.

Outside the window we see the Mosler Safe Company of Hamilton, Ohio – the “H” in the CH&D RR. We even see a strange canal boat, fright transport usually towed by a mule but here sporting an oversized cabin with stylized smoke curling like the black coal soot from the proud nineteenth-century factories. In a very real sense, the Pullman Porters who brought such dignity to the wood-paneled, velvet-seated Pullman coaches transferred the sensibilities of the second-floor steamboat cabin to the rails.

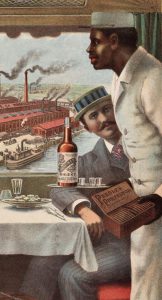

More careful examination of the blown-up detail comes even closer to home. With one hand the white-coated porter offers Perfecto cigars from the Peebles grocery which gave its name to Peebles Corner in Walnut Hills; with the other he displays a bottle of whiskey, aged and bottled by the same Joseph R. Peebles’ Sons. The porter, too, may well have been based in Cincinnati and even in Walnut Hills. Indeed, it is fair to wonder to what extent the Black Porter in the poster was intended to be just another prop in the picture. But that is a slightly different story. We shall return in a later post to the very real Pullman Porters in Cincinnati and Walnut Hills.

Geoff Sutton

See all the topics about Lincoln Avenue in the 1870’s and 1880’s.