Model Drug Store Walnut Hills Branch: what professional success looked like

Model Drug Stores, the largest chain of Black-owned pharmacies in Cincinnati during the 1910s through the 1930s, established one of its first outlets in a segregated housing complex in Walnut Hills known as Washington Terrace. It is well documented that the extensively planned development, built by Jacob G. Schmidlapp’s Model Homes Company, included club, recreation, and meeting rooms, and a cooperative grocery store sponsored and run by the management. Less noted, one building on Kerper Avenue originally housed two units labelled “Drugs” and “[Doctor’s] Office.” Unlike the other community amenities, these medical businesses were owned and managed by African American professionals. (Unlike the Model Drug branches purchased in the old West End, the chain rented the initial Walnut Hills location.)

Model Drug Stores, the largest chain of Black-owned pharmacies in Cincinnati during the 1910s through the 1930s, established one of its first outlets in a segregated housing complex in Walnut Hills known as Washington Terrace. It is well documented that the extensively planned development, built by Jacob G. Schmidlapp’s Model Homes Company, included club, recreation, and meeting rooms, and a cooperative grocery store sponsored and run by the management. Less noted, one building on Kerper Avenue originally housed two units labelled “Drugs” and “[Doctor’s] Office.” Unlike the other community amenities, these medical businesses were owned and managed by African American professionals. (Unlike the Model Drug branches purchased in the old West End, the chain rented the initial Walnut Hills location.)

A century ago, as now, there was a tremendous shortage of housing in the city and our neighborhood. The shortage was, and is, especially acute for poor people of any race or ethnicity, and for African Americans of any economic status. The Great Migration of poor African Americans from the agricultural South to the Industrial North created a crisis in many northern cities. The Progressive Era in Cincinnati did provide an imperfect response. The Model Drug Store at Washington Terrace is one neglected piece in the puzzle of the Model Homes strategy of building a segregated, self-contained community. It is not clear whether the pharmacy took its name from the socially responsible Model Homes Company that developed the neighborhood, but that would be an obvious possibility. The presence of Model Drug offers significant insights into the Model Homes community.

Let us be clear that segregation was and is a terribly destructive thing. Schmidlapp’s patronizing attitude and casual prejudice in his essays about affordable housing make it easy to project the worst aspects of mid-century segregated housing projects back onto the work in the 1910s – concentrated poverty in substandard buildings breeding unhealthy conditions both physically and psychologically. Schmidlapp indeed made these mistakes in his earliest buildings. His first small development for African Americans in Walnut Hills was criticized by the Black doctor Louis Cornish as “those prison-like tenements on the Southeast corner of Park Avenue and Chapel Street” – the same block as Douglass School. Yet in 1916, Dr. Cornish conceded, “later developments have caused you to be forgiven for that.” The Gordon Terrace Apartments on Ashland at Chapel provided larger and more dignified and comfortable apartments. The nearly 200 units in Washington Terrace west of Gilbert Avenue and north of what is now Martin Luther King Drive.

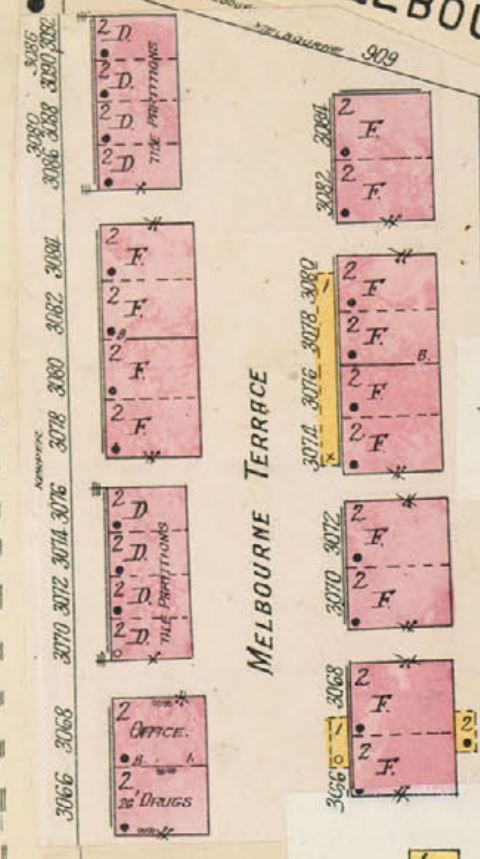

The original Walnut Hills branch of Model Drug opened in 1916 at 3066 Kerper in a new Model Homes development in Washington Terrace. Located on Kerper Avenue, the 8-building, roughly 24-unit brick section was known as Melbourne Terrace. (It is the only surviving segment of Washington Terrace, now known as the Kerper Apartments.) The African American pharmacists in ownership and executive roles, Robert D. Russell and George R. Hicks, both lived in units in the building behind the pharmacy at the time of its opening. (The exact configuration is unclear since the street numbering system is rather confusing.) The office at 3068 Kerper, in the same building as the drug store, housed Dr. Edward E. Gray’s medical practice. We have seen that Gray was one of two Black physicians who partnered with the pharmacists to create Model Drug. Gray too lived in the complex, probably in an apartment attached to the office – the building has four entrances now numbered 3066 A and B, and 3068 A and B.

The original Walnut Hills branch of Model Drug opened in 1916 at 3066 Kerper in a new Model Homes development in Washington Terrace. Located on Kerper Avenue, the 8-building, roughly 24-unit brick section was known as Melbourne Terrace. (It is the only surviving segment of Washington Terrace, now known as the Kerper Apartments.) The African American pharmacists in ownership and executive roles, Robert D. Russell and George R. Hicks, both lived in units in the building behind the pharmacy at the time of its opening. (The exact configuration is unclear since the street numbering system is rather confusing.) The office at 3068 Kerper, in the same building as the drug store, housed Dr. Edward E. Gray’s medical practice. We have seen that Gray was one of two Black physicians who partnered with the pharmacists to create Model Drug. Gray too lived in the complex, probably in an apartment attached to the office – the building has four entrances now numbered 3066 A and B, and 3068 A and B.

Just as significant, the health professionals running the pharmacy and doctor’s office, in a building dedicated to those purposes, show that the Model Homes management had experience with successful Black businessmen. This makes all the more surprising Schmidlapp’s rather public complaints that he was unable to hire suitable Black managers for the Washington Terrace Cooperative Grocery and the Gordon Hotel on Chapel Street. In fact, Sudduth’s later operation of a cooperative grocery at the corner of Chapel and Ashland, part of the Walnut Hills Enterprise Corporation, and his later Manse Hotel on Chapel at Monfort clearly demonstrate talented employees were available. The pharmacy and office both operated in the building on Kerper well after Schmidlapp’s death in late 1919.

All the while, as we have seen, the Model Drug chain grew, adding stores and Black employees both professional and retail. The corporation conducted its real estate purchases through Horace Sudduth, the most substantial businessman in the African American community, who had worked with Schmidlapp on the fundraising campaign for the Black Ninth Street YMCA. Rather than seeing the collaboration between Model Homes and Model Drug as a failure of any sort, we can understand it as a demonstration that in a Black community largely segregated by a white philanthropist, a mix of working and professional tenants could and did support appropriate health facilities for the Washington Terrace complex and more.

Washington Terrace, like the community around the old Frederick Douglass segregated school half-a-dozen blocks away, constituted a coherent, middle-class neighborhood. Its Black-owned Model Pharmacy, like African American Archibald Dickerson’s Walnut Hills Pharmacy on Chapel Street across from the school, employed Black pharmacists and other retail workers. Both pharmacies also enjoyed investments, and referrals, from young Black doctors who lived and practiced in Walnut Hills. Far from the failures of mid-century Projects, both the older community and the new development flourished for generations.

– Geoff Sutton