We have met the Italian-born sculptor Louis Rebisso, who lived on Lincoln Avenue in Walnut Hills, in the context of his first major public work in Cincinnati, the Odd Fellows Monument in Spring Grove Cemetery erected in 1881. It was not his first important American commission. Rebisso was better known as a sculptor of bronze equestrian statues, larger-than-life men on even larger horses, an increasingly popular monumental style in the half-century after the Civil War.

To skip to the end of the present story, Rebisso’s first such monument, cast in Philadelphia in 1876, was dedicated in Washington DC on October 18 that year, to critical acclaim. Harper’s Weekly, the closest thing to a standard in taste in the US, declared under the headline “The M’Pherson Statue”

To skip to the end of the present story, Rebisso’s first such monument, cast in Philadelphia in 1876, was dedicated in Washington DC on October 18 that year, to critical acclaim. Harper’s Weekly, the closest thing to a standard in taste in the US, declared under the headline “The M’Pherson Statue”

It is an equestrian figure, heroic in size. It is mounted upon a massive granite pedestal handsomely designed. M’Pherson is represented as viewing the field of battle. He grasps the check reins of the spirited horse on which he is mounted in this left hand, and his right hand holds a field-glass which he appears to have just removed from his eyes. The figure is turned facing the west, toward which the general is represented as anxiously looking. The position is an easy and a natural one.

What is important about the review is the way in which the critic saw the statue as a moment captured from frenetic motion. The horse is spirited, the reins check its charge, the field glass at the general’s side has just moved from his eyes. Rebisso’s statue, by the early twentieth century one of the most highly regard of the twenty or so equestrian decorations in the Federal District, made his reputation.

An equestrian monument in the nineteenth century was a tricky thing: the public judged horseflesh if anything more critically than human statuary. The western European world had a centuries-long tradition of equestrian monuments; as an art student in Italy, the young Rebisso would certainly have studied the horses and their riders, understanding the conventions of the form. Americans deprived of the grand tour had no such guides.

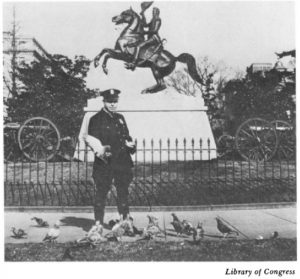

Indeed, the first American bronze of a man on a horse appeared only in 1853, portraying Andrew Jackson on a rearing mount. The sculptor Clark Mills had made his reputation creating busts. His success depended mostly on a technological breakthrough in the formulation of a plaster for creating life masks – plaster masks smeared on the oiled face of a living subject – from which to produce the (usually plaster) casts fashioned into a bust. Mills similarly saw the Jackson monument primarily as an exercise in the science of statics, getting the horse, and the rider, to balance directly above the rear hooves. That showed in the product.

Indeed, the first American bronze of a man on a horse appeared only in 1853, portraying Andrew Jackson on a rearing mount. The sculptor Clark Mills had made his reputation creating busts. His success depended mostly on a technological breakthrough in the formulation of a plaster for creating life masks – plaster masks smeared on the oiled face of a living subject – from which to produce the (usually plaster) casts fashioned into a bust. Mills similarly saw the Jackson monument primarily as an exercise in the science of statics, getting the horse, and the rider, to balance directly above the rear hooves. That showed in the product.

Mills trained his own horse to balance on his hind legs and used the beast in this circus pose as the model for the equestrian part of the group. Similarly, he placed the rider (as he showed with models) exactly above the center of gravity of the horse. With the grouping standing still, as statues do, Mills had the perfect solution. Yet the dynamic moment ostensibly captured as the horse reared up made it just as likely that the whole assembly, were it to come to life, would topple over backwards as to resume any forward progress. Nor were the critics kind about his Jackson. But Mills did produce an equestrian statue, and not everyone produces an equestrian statue. The effort led to another commission for a mounted George Washington. The horse, posed as in David’s painting of Napoleon crossing the Alps with a strong tailwind, looks a bit like Wile E. Cayote having just backed over a cliff. But it remains in our capital, in Washington Circle.

Rebisso’s first effort in the monumental style came almost by accident, just a few years after his arrival in Walnut Hills. General James B. McPherson, an Ohioan, was among the highest-ranking Union officers to die in a Civil War battle, during the siege of Atlanta in 1864. The Army of Tennessee determined at the end of the war to build a monument in their fallen commander’s honor in his hometown and gravesite in Clyde, Ohio, just south of Sandusky Bay. Cincinnatian Andrew Hickenlooper, an artillery officer under McPherson, took charge of the project. He first tried to engage the Cincinnatian Hiram Powers, nurtured in the 1830s by Nicolas Longworth, to produce the sculpture. The aging Powers had been working in Italy for decades; he was willing to oblige but required more money than the Army of Tennessee had raised. Hickenlooper therefore offered the commission to Thomas D. Jones, Ohio’s most prominent sculptor. When approached in 1867 the artist signed a contract but required time to finish a bust of President Lincoln in marble for the Ohio Statehouse. In 1871, still busy, Jones announced he would be unable to complete the monument to the fallen general.

Rebisso’s first effort in the monumental style came almost by accident, just a few years after his arrival in Walnut Hills. General James B. McPherson, an Ohioan, was among the highest-ranking Union officers to die in a Civil War battle, during the siege of Atlanta in 1864. The Army of Tennessee determined at the end of the war to build a monument in their fallen commander’s honor in his hometown and gravesite in Clyde, Ohio, just south of Sandusky Bay. Cincinnatian Andrew Hickenlooper, an artillery officer under McPherson, took charge of the project. He first tried to engage the Cincinnatian Hiram Powers, nurtured in the 1830s by Nicolas Longworth, to produce the sculpture. The aging Powers had been working in Italy for decades; he was willing to oblige but required more money than the Army of Tennessee had raised. Hickenlooper therefore offered the commission to Thomas D. Jones, Ohio’s most prominent sculptor. When approached in 1867 the artist signed a contract but required time to finish a bust of President Lincoln in marble for the Ohio Statehouse. In 1871, still busy, Jones announced he would be unable to complete the monument to the fallen general.

Hickenlooper turned to the untested Rebisso to take over the job, specifying an 8-foot height for McPherson and a proportional horse. To speed the project, the contract insisted that the sculptor accept no other commissions before the equestrian statue was done and paid an $80 monthly stipend instead of the more common lump sums upon the completion of various phases. The cost of services included an allocation of $40 for a man “to stand as a model,” while the allowance for a horse for the same purpose was half again as much at $60. More significantly for the sculptor’s career (and, as we shall see in another post, for his mostly Black neighborhood), Hickenlooper paid $630 for a studio behind Rebisso’s house, midblock between what are now Lincoln and Foraker Avenues. The sum was around the value of a house in the immediate neighborhood. It was in that proto-garage studio that Rebisso produced his first masterpiece.

The only real controversy about Rebisso’s mounted McPherson surrounded its location. The people of Clyde felt slighted when the monument went to Washington. But that is another story.