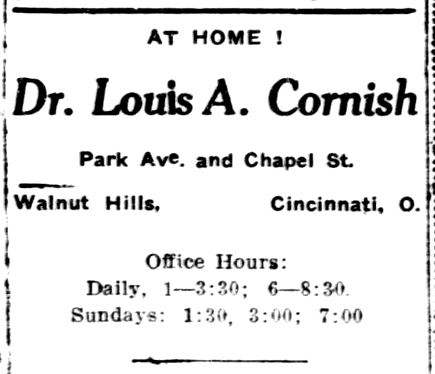

Louis A. Cornish (1872-1940) earned his MD from the African American Howard Medical School in 1898. The son of an official in the federal Bureau of Engraving, he grew up in the Black aristocracy of Washington DC, well-educated and reasonably affluent. The year after his graduation Cornish married and moved to Cincinnati. His wife Lillian was listed in the 1900 census as a musician and later offered piano lessons from their home. The couple rented a house, with room for an office, on the primarily Black Chapel Street across from the Walnut Hills Colored School, soon to be renamed Frederick Douglass School. In 1904 the couple moved their combined residence and office a block west, to 1019 Chapel, a large frame house they purchased, with space for an office and also for a boarder. A decade later the Cornishes built a substantial brick house with a wrap-around porch that still stands at 2829 Park Avenue, originally in the side yard of the office building. Dr. Cornish continued to practice in the Chapel Street office, but the living spaces there were turned into three rental apartments.

Louis Cornish quickly found his way into the African American social and business elite of the Queen City. He made an early friendship with Wendell Dabney, a wealthy businessman, city official, and journalist. Already in January 1901, Cornish joined Dabney, Black banker Robert D. S. Troy and half a dozen other (mostly medical) men in the community to incorporate a (short-lived) Savings Bank in the Dumas Hotel owned by Dabney on McAlister Street in the old downtown East End. In 1904 Cornish also had some involvement in another brief Dabney venture, a gymnasium in the Dumas. Occasional newspaper reports have him at dinners with the likes of photographer Alexander Thomas, former Gaines High School teachers Lewis D. Easton, Charles Bell and George Jackson, and community leader Fountain Lewis. Cornish was also elected Vice Chancellor of the Garnett Lodge of the Knights of Pythias, a prominent Black fraternal organization.

Cornish also joined a growing number of Black doctors, mostly trained elsewhere, in Cincinnati. In 1903 several from the group banded together to form a hospital. Louis Cornish specialized in diseases of the eye, ear, nose, and throat. His colleagues included Dr Norval Vaughan, another Howard Medical graduate living and practicing in Walnut Hills; Dr. E. Duval Colley, surgery; Dr. Frank Johnson, gynecology; and Dr. W. B. Kerr, obstetrics. The house at 421 West Ninth Street in the old West End served as a hospital for only a few years, the first of many more or less successful hospitals which allowed African Americans to practice through the early 1920s.

Cornish also joined a growing number of Black doctors, mostly trained elsewhere, in Cincinnati. In 1903 several from the group banded together to form a hospital. Louis Cornish specialized in diseases of the eye, ear, nose, and throat. His colleagues included Dr Norval Vaughan, another Howard Medical graduate living and practicing in Walnut Hills; Dr. E. Duval Colley, surgery; Dr. Frank Johnson, gynecology; and Dr. W. B. Kerr, obstetrics. The house at 421 West Ninth Street in the old West End served as a hospital for only a few years, the first of many more or less successful hospitals which allowed African Americans to practice through the early 1920s.

In 1908, along with the banker’s son Robert D. G. Troy and Dr. Norval Vaughan, Cornish partnered with pharmacist Archibald Dickerson in the Walnut Hills Pharmacy at 1126 Chapel Street. The Drug Store, just a block from the Cornish home, became a fixture in the Black community. Both Cornish and Dickerson rose as outspoken leaders in the proud community around the large new building for Frederick Douglass School completed in 1911. In 1917, both pharmacist Archibald Dickerson and Dr. Louis Cornish enlisted in the army. They reported at the Colored Medical Officer’s Training Camp in Ft. Des Moines Iowa, but both were discharged before the unit deployed to France.

Cornish saw himself as a Black professional, and he spoke truth to white power. In 1909, he responded to a city report condemning urban Blacks “and their carelessness concerning all sanitary laws” as a menace to public health. In a letter to the editor printed in the Lancet-Clinic, a national medical journal published in Cincinnati, Cornish recognized the public health disaster in the city basin. Yet he saw it as a consequence of unsanitary, overcrowded, ill-ventilated housing, streets and sewers. Tuberculosis presented the greatest challenge. The Black doctor noted “other nationalities who are just as notoriously unsanitary” living in the same neighborhood suffered the same morbidities. Contrary to many white public health pronouncements, Cornish understood the disease was a not scourge occasionally visited upon the white middle class by “the negro.” Rather, he contended, it was a scourge visited upon the poor by the failures of the public health department to properly inspect and enforce housing laws and by extension to the landlords who rented the properties to vulnerable tenants.

One of the first attempts by white progressives to ameliorate the unhealthy “Negro tenement” housing in the city basin came in 1912 across the street from the Cornishes’ home and office. Retired white banker Jacob Schmidlapp made his first attempt to provide affordable rental housing to his Black neighbors by constructing three buildings on Chapel Street with small and spartan but modern, sanitary three-room apartments with private entrances, bathrooms, and hot and cold running water. Cornish realized that Schmidlapp misjudged and devalued his neighborhood. The doctor characterized the construction as “those prison-like tenements … with their wash-tub baths and other inconveniences.” The building began a dialogue in the built environment between Schmidlapp and the leadership of the Black community that led mostly to well-received, middle-class housing.

Cornish was equally critical of the white medical establishment in its treatment of Black patients. A report on the conditions of midwifery and maternal health in Cincinnati published in 1915 quoted Dr. Cornish extensively. His most scathing criticisms were aimed at the (white) maternity organizations: “A student at the bedside with a book in hand trying to diagnose a position is really a little too primitive.” Dr. Louis Stricker, the white author of the report, acknowledged “that students should not go out and attend obstetrical work until they are known to be sufficiently advanced to be entrusted with so serious and sacred a duty.”