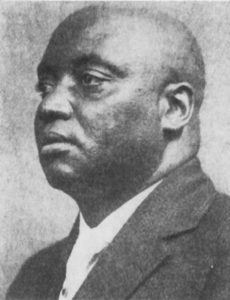

Horace Sudduth has generally been cast as a businessman who steered clear of politics. In 1921, however, Sudduth was willing to run for Cincinnati City Council. That year was near the bottom for Black political fortunes in the country and in Cincinnati. In the last throes of the Republican bossism, all nominating decisions were made by the party apparatus. Reinforced by the Great Migration of Southern agricultural workers to the industrial North, the Black community decided to act on its own.

Horace Sudduth has generally been cast as a businessman who steered clear of politics. In 1921, however, Sudduth was willing to run for Cincinnati City Council. That year was near the bottom for Black political fortunes in the country and in Cincinnati. In the last throes of the Republican bossism, all nominating decisions were made by the party apparatus. Reinforced by the Great Migration of Southern agricultural workers to the industrial North, the Black community decided to act on its own.

As Wendell Dabney put it in his newspaper, The Union, the Eighteenth Ward in the West End “was entitled to a Colored Councilman. … The spirit of discontent brewing for several years, held in check by the [First World] War and the outrageous Democratic policies of Wilson at last culminated” in a Ward meeting. “With the immense Colored Vote there was no real reason why white men should hold practically all of the offices, while the Colored men did all of the Voting.” Dabney especially pointed to a “change from the old days when gambling saloons and females of easy virtue were given the right of way in exchange for the vote.” Sudduth, identified by Dabney as “Our Real Estate Agent,” pointed out that the 18th Ward “now was largely composed of a different class of Colored Citizens. That the Workingman, the Churchman, the Southern man who had fled Northward for more freedom all constituted a mass of citizens who wanted their legal and civic rights.” The African American community, with Dabney at their head, saw Sudduth as the sort of “reputable Colored man” to represent the district.

The details of his brief campaign are as fascinating as they are disheartening. The Cincinnati Enquirer headlined their coverage of the April 2, 1921 meeting “NEGROES CHOOSE CANDIDATE.” The meeting was held in a church in the Ward, but it was called by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) – the international Black Separatist organization headed by the Jamaican immigrant Marcus Garvey. At the meeting, a UNIA national official from Philadelphia spoke for the party. William Ware, the head of the organization’s Cincinnati Division, supported Sudduth. The Enquirer coverage concluded: “observers said the political movement of the negroes was the most formidable they have attempted in Cincinnati.” This collaboration of Dabney (the head of the local NAACP as well as the editor of The Union) and Ware (of UNIA) and the real estate mogul Sudduth – let alone with the Republican machine – must be one of the most remarkable political collections of “Race Men” in the 1920s.

The details of his brief campaign are as fascinating as they are disheartening. The Cincinnati Enquirer headlined their coverage of the April 2, 1921 meeting “NEGROES CHOOSE CANDIDATE.” The meeting was held in a church in the Ward, but it was called by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) – the international Black Separatist organization headed by the Jamaican immigrant Marcus Garvey. At the meeting, a UNIA national official from Philadelphia spoke for the party. William Ware, the head of the organization’s Cincinnati Division, supported Sudduth. The Enquirer coverage concluded: “observers said the political movement of the negroes was the most formidable they have attempted in Cincinnati.” This collaboration of Dabney (the head of the local NAACP as well as the editor of The Union) and Ware (of UNIA) and the real estate mogul Sudduth – let alone with the Republican machine – must be one of the most remarkable political collections of “Race Men” in the 1920s.

But it was not to be. Sudduth told the community in a letter to The Union on June 11, “When the crucial moment came, I was very much surprised and shocked to find THAT I HAD BEEN MISINFORMED AND COULD NOT RUN IN THE EIGHTEENTH WARD!” The white Republican nominating board had welcomed the 18th Ward’s Black recommendation, but discovered, they said, that Sudduth had voted in the previous election in a different Ward – curiously, the 4th, in Walnut Hills – and regretted they could not endorse the Black champion. In his stead, they ran a white man, John Burckhauser, who won the election, as Republicans still inevitably did. The party made its bad faith toward Sudduth and toward the Black community clear when they repeated Burckhauser’s nomination in 1923.

In 1925, Cincinnati passed a new City Charter, changing from the Ward-based system that had enabled the Republican machine, to city-wide “at large” elections. William Ware’s local UNIA Division supported the new Charter, seeing it as the best route toward Black municipal representation. While the updated charter disrupted the ailing machine corruption, it also eliminated the Black majority ward in the West End and put off for another six years the election of a Black representative – a Republican – to the council. Sudduth for his part remained active in politics. He continued to operate as a Republican; in 1930, for example, he joined Robert A. Taft on the nominating committee of the Republican Party for state and county offices. Sudduth may have exercised some influence behind the scenes, but he was never again a serious candidate.

In 1925, Cincinnati passed a new City Charter, changing from the Ward-based system that had enabled the Republican machine, to city-wide “at large” elections. William Ware’s local UNIA Division supported the new Charter, seeing it as the best route toward Black municipal representation. While the updated charter disrupted the ailing machine corruption, it also eliminated the Black majority ward in the West End and put off for another six years the election of a Black representative – a Republican – to the council. Sudduth for his part remained active in politics. He continued to operate as a Republican; in 1930, for example, he joined Robert A. Taft on the nominating committee of the Republican Party for state and county offices. Sudduth may have exercised some influence behind the scenes, but he was never again a serious candidate.

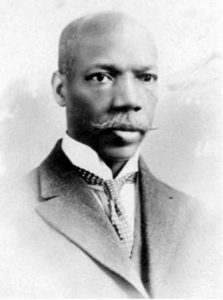

The role of the UNIA in the 1921 council election says more about Black community solidarity in the wake of the First World War and the Wilson administration than it does about Sudduth. Cincinnati’s disproportionately large Division (at its height it claimed 8,000 members) did not in fact reflect the organizing talents of Marcus Garvey or his international movement in the city. William Ware had arrived in Cincinnati from Louisville in 1908, and worked as an organizer in the West End, initially through the Antioch Baptist Church. In 1917 he established the Welfare Association for the Colored People of Cincinnati. Ware travelled to New York in 1920 for Garvey’s organizing convention for his world-wide movement of Black Peoples; he returned to Cincinnati a Garveyite and converted his Welfare Association into the Cincinnati Division of UNIA. Ware remained a loyal Garvey supporter even after the naïve failure of the Black Star Steamship Line a few years later. Garvey’s influence waned after imprisonment in the US and deportation to Jamaica. In Cincinnati, Ware definitively split with Garvey after the latter moved to Jamaica. Nonetheless, Ware remained an important organizer in the West End through the early 1930’s, notably as an advocate for Black students attending integrated schools.