Recent events have drawn attention once again to the famous Hayes-Tilden election in 1876 when Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes became president. (We shall return to Hayes in his earlier career in our city, including a brief stint in Walnut Hills, in the next post.) He faced New York Democratic Governor Samuel Tilden; in an age generally characterized as the nadir of political corruption, both candidates nonetheless had reputations for integrity. The Republicans (the party of Lincoln, Grant, and Hayes) had enacted the Fifteenth Amendment that promised the Black franchise over the objections of southern Democrats. Hayes in fact served as the Governor of Ohio in 1869 when Amendment came to the state for ratification; his first attempt to pass it failed in the Democratic legislature, but the state election that fall brought in a new Republican majority and Hayes shepherded it though in 1870.

Recent events have drawn attention once again to the famous Hayes-Tilden election in 1876 when Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes became president. (We shall return to Hayes in his earlier career in our city, including a brief stint in Walnut Hills, in the next post.) He faced New York Democratic Governor Samuel Tilden; in an age generally characterized as the nadir of political corruption, both candidates nonetheless had reputations for integrity. The Republicans (the party of Lincoln, Grant, and Hayes) had enacted the Fifteenth Amendment that promised the Black franchise over the objections of southern Democrats. Hayes in fact served as the Governor of Ohio in 1869 when Amendment came to the state for ratification; his first attempt to pass it failed in the Democratic legislature, but the state election that fall brought in a new Republican majority and Hayes shepherded it though in 1870.

Despite President Grant’s best efforts, voter intimidation played a huge role in the election of 1876. Southern Republicans, including those Black voters able to vote, went for Hayes. Yet the election was close and contested. Tilden won the popular vote by a little more than two percent nationally – about the same margin as Clinton’s popular vote margin over Trump in 2016. The key to both elections lay in the electoral college. In 1876, Florida, South Carolina, and Louisiana were already in the only southern states still ruled by reconstructed governments and honoring Black suffrage. In each, both parties claimed victory and sent competing slates to the electoral college. (It is worth pointing out that the Republican slate from Louisiana, at least, was put forth by a canvassing board with two Black members.) Moreover, Hayes won Oregon with its three electoral votes. One of the Hayes electors was disqualified on a questionable technicality by the Democratic governor, who (with no particular argument) appointed a Democrat in his stead.

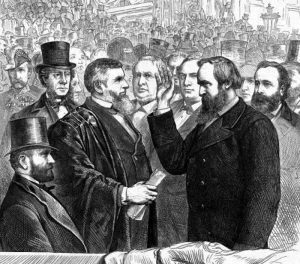

Hayes needed all the contested votes to squeak by to victory. The constitution specified that a joint session of congress should receive the electoral votes and count them. The House and Senate had no constitutional or statutory guidance on how to do that. Some suggested that the Vice President, presiding over the joint session, should choose which electors to recognize, but in that direction lay the prospect that the sitting vice president might always choose his favored electors and thus the next president. Congress passed legislation, which President Grant signed, to appoint an electoral commission, with five members from each house and five judges. The fifteen included seven members from each party and one judge from Illinois without party affiliation. The plan was apparently for him to broker a deal. The Illinois legislature put an end to that veneer of neutrality by electing him as a Republican Senator. He withdrew from the commission, but a Republican, another judge, took his place. The commission split on party lines to recommend that congress should award the electoral votes to Hayes, giving him a single-vote majority in the electoral college.

Hayes needed all the contested votes to squeak by to victory. The constitution specified that a joint session of congress should receive the electoral votes and count them. The House and Senate had no constitutional or statutory guidance on how to do that. Some suggested that the Vice President, presiding over the joint session, should choose which electors to recognize, but in that direction lay the prospect that the sitting vice president might always choose his favored electors and thus the next president. Congress passed legislation, which President Grant signed, to appoint an electoral commission, with five members from each house and five judges. The fifteen included seven members from each party and one judge from Illinois without party affiliation. The plan was apparently for him to broker a deal. The Illinois legislature put an end to that veneer of neutrality by electing him as a Republican Senator. He withdrew from the commission, but a Republican, another judge, took his place. The commission split on party lines to recommend that congress should award the electoral votes to Hayes, giving him a single-vote majority in the electoral college.

Yet the story is not so simple. That conservative bulwark Lindsey Graham, of all people, pointed out this week that the electoral commission established in 1876 to settle the dispute was a failure.

“It didn’t work. Nobody accepted it. The way it ended is when Hayes did a deal with these 3 states – you give me the electors; I’ll kick the Union Army out. The rest is history. It led to Jim Crow.”

Had Hayes not made his deal with the southern states, Congressional Democrats (who controlled the House) would have filibustered to avoid the Commission’s recommendation. The deal described did make Hayes president and, as Graham observed, it ended Reconstruction and led to the Jim Crow system of suppression of Black votes and Black rights for nearly a century.

Hayes maintained his integrity, perhaps, by keeping his promise to remove the Union Army from the south, despite his sincere and consistent efforts otherwise to support Black civil and voting rights throughout his career. The southerners who promised Hayes that in return for the removal of the troops they would protect the Black franchise reneged. The bargain thus laid bare the dangers of last-minute back-room deal-making to settle an election.

It was in the wake of the 1876 debacle, and close elections in 1880 and 1884, that Congress passed an act in 1887 to provide clear electoral college selection rules. The law conceded every point at issue in 1776 to the Jim Crow South. States rather than the Congress would determine the selection of electors; the governor’s timely certification of the electors and their votes could not be questioned by Congress. Had this States’ Rights policy been in effect in 1876, no bargain would have been required and the election would have gone to Tilden. In exchange for Hayes’ single term, for nearly a century the system allowed the former Confederate States to ignore the Reconstruction Amendments that guaranteed equal rights and protection to African Americans. But for the twentieth century, at least, the rules prevented “corrupt bargains” that plagued the nineteenth from entering into the last step of the presidential election process.