Black engineer Granville T Woods spent a crucial decade in Cincinnati beginning in the early 1880’s, devising and patenting inventions mostly at the intersection of electricity and railroads. To dispense quickly with the Walnut Hills connection, Woods never lived in our neighborhood; for a while, he made his home on Fulton Avenue near the foot of Kemper Lane and that address is sometime confused with the Fulton near Eden Park. Nor did he work directly on the first experimental electric streetcar line in Walnut Hills. Woods discussed using a system he had patented with the entrepreneur who built the line, George Kerper. Moreover, Woods held a patent on the electrical connection between the car and the overhead power lines that was used on that line. But wealthy Cincinnati partners in the Woods Electric Company held out for more money for Woods’ patents, and Kerper used a competing electrical system.

Black engineer Granville T Woods spent a crucial decade in Cincinnati beginning in the early 1880’s, devising and patenting inventions mostly at the intersection of electricity and railroads. To dispense quickly with the Walnut Hills connection, Woods never lived in our neighborhood; for a while, he made his home on Fulton Avenue near the foot of Kemper Lane and that address is sometime confused with the Fulton near Eden Park. Nor did he work directly on the first experimental electric streetcar line in Walnut Hills. Woods discussed using a system he had patented with the entrepreneur who built the line, George Kerper. Moreover, Woods held a patent on the electrical connection between the car and the overhead power lines that was used on that line. But wealthy Cincinnati partners in the Woods Electric Company held out for more money for Woods’ patents, and Kerper used a competing electrical system.

We will see in this series of posts that Woods’ work in Cincinnati, with a unique combination of technical and legal challenges, shaped with way he approached the engineering problems surrounding his patents on various electrical transmission and control systems used on street railroads. He also invented a wireless communication system that allowed moving trains to communicate with stations and with each other, and several more safety devices for railroads and electric circuits.

But Woods did one at least one occasion give a lecture about electricity and magnetism in Walnut Hills. At any rate, he was important enough in the electric streetcar industry, and streetcar lines were important enough to the development of Walnut Hills, that it’s worth a look at his biography and his inventions.

Granville T. Woods in Ohio: Connections to the Black Community

Granville T. Woods, who lived in Cincinnati in the 1880’s, has been practically defined as an engineer. Yet he also lived as Black man in the nineteenth century – born free before the Civil War, he came of age in the era of reconstruction and his career matured under increasing Jim Crow oppression. Fortunately, a Black Brooklyn bus driver and historian named David Head has brought more attention to Woods as a man struggling to make his way in Reconstruction and Jim Crow America. Head’s common-sense work with standard sources like the census has unearthed the straightforward biography that Woods himself was at pains to conceal later in life.

Granville’s father Cyrus, a wood sawyer born in Tennessee in about 1810, owned some property in and around the central Ohio town of Monroe. His mother, from Virginia, was widowed with three children before she married Cyrus. She worked as a washerwoman. It is not clear how either one of the parents came to live in the free state of Ohio. In June 1850, the census showed the family had grown to include five children — but did not yet enumerate Granville. The Woodses lived in a cluster of three Black families; the Census book noted only a few other single individuals in the neighborhood notated with the color “B.”

Census records from 1860 (still in the town of Monroe) and 1870 (in Columbus) indicate that Granville was born in 1850 or 1851. His father Cyrus, perhaps a sometime preacher, lived to see emancipation, although he died in 1866. Granville and his parents, and perhaps his younger brother William, appear sporadically in Columbus city directories through the 1850’s, ‘60’s and early ‘70’s – the sort of sketchy paper trail left by most working people. (The trail is a little trampled by overuse; another, white, Granville Woods was born a few years later and lived in the same area, and a second Black Granville Woods from Virginia, about ten years older, lived in Salem in northeastern Ohio. Moreover, the 1870 Census lookups sometimes misspell “Woods” as “Woode.”)

The community in Columbus in 1870 portrayed by the census was substantially integrated – enough so that the enumerator took the trouble to fill in all the race boxes with “B”, “W”, or “M” for mulatto – people of visibly mixed race. It is also striking that many of Granville’s neighbors of color held middle class jobs, some requiring mechanical skills (“Runs Stationary [steam] Engine”, “Works in Machine Shop,” “Works in Sawmill,” “Journeyman Blacksmith,” “Journeyman Plumber,” “Journeyman Bricklayer,” “Journeyman Paperhanger,” “Works at Tannery”) and others quite respectable and relatively lucrative (Grocer, Barber) . Most women in male-headed households had their occupations listed as “at home,” indicating that they did not work outside of it or take in work – then as for another century a sign of middle-class security. To be sure there were also a couple of Teamsters and a couple of Laborers; women who headed their households (including Granville’s widowed mother in 1870) generally worked as “Washerwoman.” On the whole, though, rather like Walnut Hills in Cincinnati, the Woods’ neighborhood in Columbus included relatively prosperous African Americans.

Granville and his mother in 1870 lived near enough to David Jenkins to appear in adjacent dwellings on the census form. Perhaps the leading Black citizen in the small Columbus community, Jenkins for a short time in the 1840’s edited the Palladium of Liberty, an abolitionist newspaper. Jenkins was also an important figure in the state-wide Black Conventions of the mid nineteenth century; he would have been well-known in Cincinnati. Active in the community’s church and masonic institutions, Jenkins welcomed Granville as a young man into a Black masonic lodge in Columbus.

Granville Woods himself appeared in the census as a “Church Sexton” –maintenance worker – a position confirmed in the Columbus City Directory of 1873. In his twenties, he also worked in a couple of carriage shops, a stint as a porter, and as a waiter. It’s impossible to know which of these jobs in the directory may have been full time, and whether they precluded other employment. The job as Sexton in the Church must have been long-term and part time, since it appears in both the 1870 census and the 1873 directory; other listings in the directory before and after included the other occupations. It is plausible that Granville spent time in some of these positions (including as a Church Sexton) among machinists, as his later biography in Simmons’s Men of Mark would indicate. He may also have found work with some of the Black men in the neighborhood holding mechanical jobs.

The employment trail in Columbus runs cold in the later 1870’s. We will pick up with solid documentation in Cincinnati beginning in 1882.

Granville T. Woods in the fabric of the Black Community in Cincinnati

When Granville T. Woods migrated to Cincinnati, he entered a larger and more established Black community than the one he had left in Columbus nearly a decade earlier. We have met many of the leading African Americans in Cincinnati in previous posts. Granville found his way into the fabric of that society. His acceptance and status were probably aided by his acquaintance with his Columbus neighbor David Jenkins. As an underground railroad operative, Jenkins would certainly have known the Black Cincinnati furniture manufacturer Henry Boyd. Likewise, Jenkins’ participation in the Black Conventions in Ohio would have put him in contact with John Gaines and Peter Clarke. Finally, Jenkins’ induction of Granville Woods into African Freemasonry would have given the younger man an immediate way into his new city’s educational elite. Peter Clark, the unrelated Samuel Clark and William H. Parham were all leading freemasons and teachers in the segregated Colored Schools. Woods was embraced by the semi-secret society.

Understanding Woods’ personal life in Ohio is more problematic. In June 1880 he married a Sadie Turner; the marriage license report in the Cincinnati Star marked is his first appearance in Cincinnati. (Other news included the Democrats uniting for General Hancock in the convention national Convention meeting in Cincinnati; the Ohio Republican James Garfield would win the election in the fall.) The city directory the next year listed Sadie Woods, laundress, working at the southeast corner of Canal and Race as well as an “S. Woods, engineer” living at the same address. It’s not clear whether those entries indicate the recently married couple or not. In 1882 Granville Woods makes his first unequivocal appearance in the directory, living on Fulton Street in the Fulton neighborhood on the near east side; there is no entry for Sadie although it was uncommon for wives to leave any evidence in the directories.

We can follow Woods around various downtown neighborhoods in the annual Williams Directories between 1882 and 1891. His footprints in the community are a little light, but he made his way into the odd gossip column. There is no indication that he entered into any business relationships with Black Cincinnatians, but very few in the community had the sort of capital required to engage in serious manufacturing.

In 1891, he was sued for divorce by an Ada Woods in the same city; some recent accounts assume that Ada and Sadie were the same woman. Another 1891 story in Cincinnati’s Enquirer – a democratic newspaper unsympathetic to Blacks, free or freed – suggest a more complicated domestic life. At any rate, accounts of Woods’ serious bout of smallpox while in Cincinnati – appearing in all places in patent litigation – refer to male acquaintances nursing him but make no mention of a wife.

Apart from inventing, there is passing mention of Granville Woods in Cincinnati in a few articles during the 1880’s. In good nineteenth-century fashion he gave lectures on electricity and magnetism in public forums in the city. One venue was the rather new YMCA (before there was a segregated Black Y), a common place for educational events. Yet Woods also lectured about his area of expertise in his own community. On one occasion he spoke in a Black Baptist Church downtown. In Walnut Hills, he gave a lecture/demonstration at Brown Chapel AME – already in the 1880’s a well-established congregation. Brown Chapel was at the time a short block away the street from the Elm Street Colored School (later Frederick Douglass) in Walnut Hills.

Apart from inventing, there is passing mention of Granville Woods in Cincinnati in a few articles during the 1880’s. In good nineteenth-century fashion he gave lectures on electricity and magnetism in public forums in the city. One venue was the rather new YMCA (before there was a segregated Black Y), a common place for educational events. Yet Woods also lectured about his area of expertise in his own community. On one occasion he spoke in a Black Baptist Church downtown. In Walnut Hills, he gave a lecture/demonstration at Brown Chapel AME – already in the 1880’s a well-established congregation. Brown Chapel was at the time a short block away the street from the Elm Street Colored School (later Frederick Douglass) in Walnut Hills.

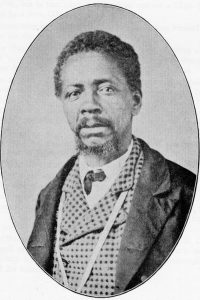

Granville T. Woods introduces himself: biography in Simmons’ Men of Mark

In 1887 a Black Baptist minister, teacher and college president in Lexington, Kentucky named William J. Simmons published Men of Mark, a collection of biographies of 172 leading African American men. It seems that Simmons lightly edited submissions by his subjects; one such man took this work as an opportunity to introduce himself as “Granville T. Woods, Esq, Electrician – Mechanical – Engineer – Manufacturer of Telephone, Telegraph and Electrical Instruments.” Woods presented a neat chronology: born in Columbus, Ohio, 1856; went to work in a machine shop there 1866; 1872, moved to Missouri to work on a railroad and study electricity in his leisure time; 1874 moved to Illinois to work in a rolling-mill; 1876, moved “East” to study electrical and mechanical engineering “at college” in the afternoons and evening after a day shift in a machine shop; 1878 to sea aboard a British steam ship; 1880, as an engineer on a Dayton, Ohio railroad and then on to a manufacturing career in Cincinnati.

In 1887 a Black Baptist minister, teacher and college president in Lexington, Kentucky named William J. Simmons published Men of Mark, a collection of biographies of 172 leading African American men. It seems that Simmons lightly edited submissions by his subjects; one such man took this work as an opportunity to introduce himself as “Granville T. Woods, Esq, Electrician – Mechanical – Engineer – Manufacturer of Telephone, Telegraph and Electrical Instruments.” Woods presented a neat chronology: born in Columbus, Ohio, 1856; went to work in a machine shop there 1866; 1872, moved to Missouri to work on a railroad and study electricity in his leisure time; 1874 moved to Illinois to work in a rolling-mill; 1876, moved “East” to study electrical and mechanical engineering “at college” in the afternoons and evening after a day shift in a machine shop; 1878 to sea aboard a British steam ship; 1880, as an engineer on a Dayton, Ohio railroad and then on to a manufacturing career in Cincinnati.

As we have seen, Ohio Census records show consistently that Woods was born about 5 years earlier than this biography suggests; his later accounts of his own life would make him younger still. It’s not clear whether the claim that he started working in a machine shop in 1866 might be true, starting at the age of about fifteen rather than the age of ten computed from the biography. The dates for other moves are also plausible: he appeared in Columbus directories consistently through 1874, and then once more in 1877. He married in Cincinnati in 1880, certainly compatible with employment on a Dayton-based railroad. On the other hand, the claims of engineering studies at college may be exaggerated; the title of engineer might likewise have dignified a position as a “fireman.”

Woods in fact proved adept at self-promotion. In this biography for Simmons’ book, he quoted a whole raft of newspaper articles touting his genius. He wrote the Cincinnati Sun reported that “Granville T. Woods, a young colored man of this city, has invented a new system of electrical motor, for street railroads. He has invented also a number of other electrical appliances, and the syndicate controlling his inventions think they have found Edison’s successor.” We shall return to this Cincinnati syndicate in a later post. The comparison between Woods and Edison continues to the present day.

The biography produced more quotes: in January 1886, The Catholic Tribune had opined “Granville T. Woods, the greatest colored inventor in the history of the race, and equal, if not superior, to any inventor in the country, is destined to revolutionize the mode of streetcar transit.” The related publication The American Catholic Tribune, possibly the same correspondent, in January 1887 had said “Mr. Woods, who is the greatest electrician in the world, still continues to add to his long list of inventions” including the Induction Telegraph. “Mr. Woods has all the patent office drawings for those devices, as your correspondent witnessed.”

In his management of the newspaper coverage Woods was absolutely in line with successful white electrical inventors. His composition of his own biography citing these flattering passages is likewise of a piece with the self-promotion practiced by the likes of Edison and Westinghouse and Tesla.

What is not clear from their titles is that the Catholic newspapers were both edited by Black Cincinnatians. Woods parlayed the stories he had provided to these friendly correspondents into evidence in a biographical sketch that is mined to this day for the quotes he provided. That is to say, Woods found in Reconstruction Cincinnati a Black community in which he had natural allies. It seemed for a short, thrilling time that he would make his way in our city as a great inventor, a rival or successor to the industrial engineers creating huge technical and corporate systems to distribute electric lights and telephones and telegraphs and railroads in a rapidly industrializing world. Like successful white inventors, he learned how to patent his ideas; unlike most rivals he also learned how to defend his intellectual property in the arcane and fast-changing system of patent law, patent interference, and patent infringement.

Woods went on in a similar vein through the whole of his Simmons biography. He quoted extensively from an 1885 article in the important magazine Scientific American that described frequent collisions on railroads and hopes for their prevention by a newly patented invention – the induction telegraph – which allowed moving trains to communicate with nearby stations, and with other moving trains. The correspondent of the Catholic Tribune had seen with his own eyes Woods’ drawings, accepted by the patent office. What Woods did not mention here was that the Scientific American article described a patent applied for by a white inventor. Woods had also applied for a patent on the device. The patent office ruled between the time of the Scientific American article and Simmons’ biography that Woods’ invention had priority, so he was claiming credit where credit was due. The passage Woods quoted from the American Catholic Tribune closed with the observation the “patent office has twice declared Mr. Woods prior inventor of the induction telegraph as against Mr. Edison, who claims to be the prior inventor. The Edison & Phelps Company are now negotiating a consolidation with Woods’ Railway Telegraph Company.” Yet the patent priority had not earned him any mention in the Scientific American, and the patent alone did not produce either devices or income; the drawn-out legal dispute ended with Woods selling the patent to the Edison interests for a relatively small sum. Yet the partial victory did provide tremendous prestige and bragging rights.

Granville T. Woods: What did success look like?

Granville T. Woods in some sense failed as an electrical inventor in Cincinnati: while he patented several brilliant inventions none of them produced much income. His wealthy white partners rarely paid him a salary and refused to manufacture any of his devices; it was in hopes of steady income backing for a factory that Woods signed up with them. We might wonder why the investors made so little effort. To be sure Woods lived and worked in the city during the 1880s – the era of the “redemption” of Confederate ideas in the South and of ever hardening Jim Crow in the North. But I don’t think that established inheritors of wealth in the Queen City would have gone to the trouble to establish the Woods Electric Company simply in order to spite a Black man. I would suggest his inability to establish himself and the corporation as major players in the nation’s emerging heavy electrical industries was as much a failure vision in Cincinnati’s business community as of anything Woods did or did not do. The city’s moneyed elite wanted sure bets to manage and market rather than venture capital opportunities.

Woods engineered competitive products on the cutting edge of emerging technologies. He also, against all odds, managed to protect his patents, especially the Induction Telegraph that allowed communications between moving trains, stations, and other trains. As Edison would do with the lightbulb, Woods also patented parts required to implement his basic invention – relays that allowed the conversion of the weak inductive coupling into a signal strong enough to actuate a telegraph sounder. It was not Woods, but the Gano-controlled board of his manufacturing concern, who failed to capitalize this essential device.

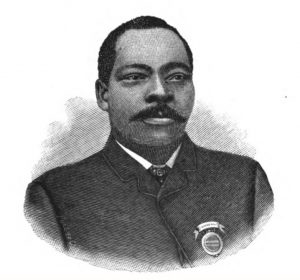

George Kerper, another Cincinnati outsider, was gambling on new transportation technologies. He had built the Mt. Adam Incline and Cincinnati’s first cable car up Gilbert Avenue. The cable car had involved new patents and designs by a young Cincinnatian who was the college-educated son of the owner of the largest machine shop west of the Alleghenies. In 1887 Kerper was working with Granville Woods to build an electric streetcar in Cincinnati. Again, Gano’s board was willing to try to sell a license Woods’ patents but unwilling to construct or underwrite an experimental electric streetcar line on May Street in Walnut Hills. The contract went instead to an inventor from upstate New York name Daft. Frank Sprague, sometime Edison power generation engineer, opened the first electric streetcar system in Richmond, Virginia in 1888. Sprague sold more than a hundred of his streetcar installations within a couple of years; Edison bought the business and manufactured the electrical components. In this case, Cincinnati’s financial powers missed what became the most lucrative municipal transportation technology for the next half-century.

Woods, perhaps convinced that the Cincinnati business community didn’t have the vision to invest in the new technologies he had mastered, left for New York. In 1890 a test track based on a new design by Woods was constructed in Coney Island, the neighborhood in Brooklyn New York that would host so many amusement parks. The system had two radical innovations. First, the power cables were carried underneath the tracks in the same sort of covered trench used for cable cars. That feature was safer and lower maintenance than conventional overhead wires and made conversion of cable cars to electric streetcars inexpensive and simple. Second, by using a sophisticated system of electro-magnetic switches (solenoids) Woods was able to insure only the contacts in the section of track under the car were electrically activated; as the car moved on the system switched the power off. This improved safety since a shovel or a cane that found its accidental way into the power slots would not carry a dangerous current to its holder. It also reduced energy losses owing to stray currents and leakage. The design was adopted, with little financial remuneration to Woods, in the Manhattan subways and elevated railways.

Woods gained the respect of the major electrical inventors and manufacturers. In New York between 1892 and his death in 1910, at the age of 59, he sold more than 20 patents in emerging technologies. These included eight electric railway patents to General Electric, three patents for electric brake controllers on trains to Westinghouse, four patents on electric motor controllers to Harry Ward Leonard – Thomas Edison’s chief of power distribution systems before he set out on his own.

As he had done when he settled in Cincinnati Woods invented a new biography in New York. Beginning in 1892 he adopted a third birthdate – 1863 – and now a second birthplace: Australia! He claimed that one grandmother was a Malay Indian and his other grandparents Australian Aborigines. It is possible, as some now suggest, that he determined to make his visible Blackness more exotic in order to escape the degrading heritage of enslaved ancestors. Yet most early accounts that commented on his ostensibly Black Australian ancestry observed that the Aborigines were even lower in the Great Chain of Being than Black Africans. Perhaps Woods, comfortable with his own genius, was playing with the Social Darwinists, defiantly proclaiming that even those labelled the lowest of humankind could thrive in its most esoteric scientific technology.

On the leadership of African Freemasonry in Cincinnati, see for example Arnett, Benjamin William Proceedings of the semi-centenary celebration of the African Methodist Episcopal Church of Cincinnati, held in Allen Temple, February 8th, 9th, and 10th, 1874 : with an account of the rise and progress of the colored schools, also a list of the charitable and benevolent societies of the city. 1874, Pp 127-128

On his divorce from Ada Woods, see an article on “Doings of the week among the Afro-Americans of the Queen City” picked up by The Appeal, St. Paul Minnesota, May 02, 1891, p. 1 https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83016810/1891-05-02/ed-1/seq-1/#date1=1870&index=4&rows=20&words=Granville+Woods&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=&date2=1915&proxtext=Granville+Woods&y=7&x=13&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=2