An old industrial building at 660 Lincoln Avenue, now used for office space by Children’s Hospital and bearing its logo, is visible from I71 as the highway reaches the top of the hill from downtown Cincinnati. The building began its life in 1914 as an assembly plant for the Model T Ford.

An old industrial building at 660 Lincoln Avenue, now used for office space by Children’s Hospital and bearing its logo, is visible from I71 as the highway reaches the top of the hill from downtown Cincinnati. The building began its life in 1914 as an assembly plant for the Model T Ford.

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Cincinnati was by far the world’s largest producer of horse-drawn vehicles – carriages, wagons and buggies. The Queen City mass produced parts like springs, suspensions and lamps, as well as completed vehicles. The assembly plants for some of the major manufacturers like Anchor buggy were among the largest industrial plants in the city. Cincinnati exported most of its products, especially to farms and towns throughout the Midwest, although Anchor also had a considerable international trade with Central and South America and even Australia. The company developed the production of a kit that could be shipped, as parts in a box, to be assembled by the distributor or even the end user; even the box constituted parts for the finished vehicle. This system kept both shipping costs and “sticker price” low.

Cincinnati had a few inventors dabbling in carriages driven by steam and gasoline engines during the 1890’s. Yet it seems that none of the major players in horse-drawn vehicles showed any serious interest in automobiles until well after the turn of the century. (Jacob Schmidlapp, owner of the first motor car in the city, remarked that Cincinnati’s topography, with steep hills and sharp turns almost anywhere one might drive, rendered the market an unlikely one.) Yet our city was an obvious place to start: buggy engineers with patents, carriage parts and accessory plants, body-building expertise, distribution systems and dealer networks seemingly invited the attachment of engines and transmissions to Cincinnati vehicles. Indeed in 1901 and 1902 both Henry Ford and the Packard brothers came to the city to try to interest the carriage industry and its financial backers in doing automobile business together, but to no avail. Cincinnati’s Anchor buggy did develop an automobile in 1910 and built 50 prototypes. The firm received 5,000 orders from its buggy sales network. (Ford by comparison sold a little over 10,000 cars in 1909.) Yet the unexpected death of one of the company’s principals at age 45 ended the project – the only realistic effort by a Cincinnati manufacturer to enter the automobile industry in a serious way during the early decades of the last century.

Henry Ford, meanwhile, had returned to Detroit, found new backers, and introduced the Model T in 1908. The simple, inexpensive car took the country by storm. Ford opened its first sales office in Cincinnati in 1909; the company had dozens of agencies in major cities by 1910. In 1911 the company built a four-story sales and service center at 911 Race Street in downtown Cincinnati. That facility served as a regional office for dealers in the area, enforcing pricing and service standards.

In 1913, the Ford company adopted a moving assembly line that decreased costs further. (It has been suggested that Ford developed the moving assembly line after studying the “disassembly lines” developed in the Cincinnati pork business fifty years earlier, later adopted by packers in Chicago.) The Highland Park Plant outside Detroit, a six-story reinforced concrete building with large windows for natural light, built the cars from the top of the factory down. The top two floors produced complex major components like engines and transmissions. The cars started on the fourth floor, acquiring more and more pieces as they moved along, bolted on by many hands along the line, emerging on the ground floor as complete vehicles. Modern Times!

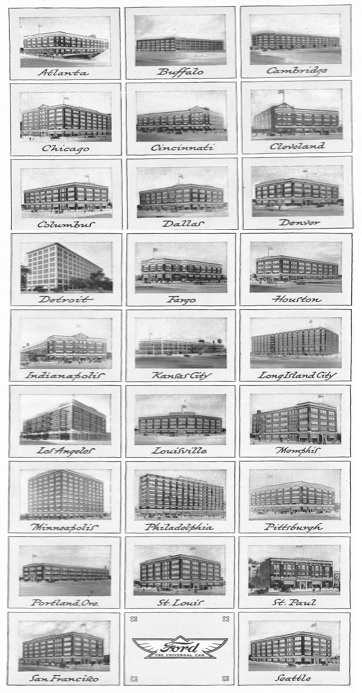

Like the Cincinnati carriage industry, Ford Motor Company had to cope with high shipping costs from its factories in Detroit. Only 3 Model T’s would fit on a railroad car. Ford adopted the vehicle kitting solution pioneered in Cincinnati. The 1913 plant near Detroit continued to produce all components including engines, gearboxes, suspensions, and metal body parts. Complete, unassembled cars were packed into boxes made from the lumber that would be used in the floorboards of the car. Eight of these kits would fit on a railroad car. Ford began building final assembly plants all over the country.

Cincinnati was an obvious site for an assembly plant for all the reasons mentioned above. In addition to railroad and river connections and established distribution systems, the city provided access to skilled, semiskilled and unskilled labor. Beyond the obvious assembly line workers, Cincinnati had a plentiful supply of educated white-collar clerks and managers to perform office functions like accounting, shipping and personnel. A railroad ran through western Walnut Hills; the area around the tracks, just east of Reading Road, served as a corridor for industry. Ford acquired a three-acre site along the rail line on Lincoln Avenue. Construction of the plant began in 1914 and production rolled off the line beginning in the spring of 1915. The Cincinnati factory (and a dozen others), while designed for the local site, duplicated the lower floors of the modern Detroit factory – the conveyor line below the component assembly areas. Cars moved along the assembly line from the top floor down. A local feature of the Cincinnati site, in densely developed Walnut Hills, included a short-term storage parking lot on the roof of the factory.

Cincinnati was an obvious site for an assembly plant for all the reasons mentioned above. In addition to railroad and river connections and established distribution systems, the city provided access to skilled, semiskilled and unskilled labor. Beyond the obvious assembly line workers, Cincinnati had a plentiful supply of educated white-collar clerks and managers to perform office functions like accounting, shipping and personnel. A railroad ran through western Walnut Hills; the area around the tracks, just east of Reading Road, served as a corridor for industry. Ford acquired a three-acre site along the rail line on Lincoln Avenue. Construction of the plant began in 1914 and production rolled off the line beginning in the spring of 1915. The Cincinnati factory (and a dozen others), while designed for the local site, duplicated the lower floors of the modern Detroit factory – the conveyor line below the component assembly areas. Cars moved along the assembly line from the top floor down. A local feature of the Cincinnati site, in densely developed Walnut Hills, included a short-term storage parking lot on the roof of the factory.

In Detroit during the Model T moving assembly line era (1913-1927) Ford developed a paternalistic relationship with production workers. The “Sociology Department” kept extensive records on employees, tracking marital status, deposits in bank accounts, school attendance of employee children, housing type and condition, and so on. In exchange, the company doubled wages to $5 per day – a wage Henry Ford calculated could make his employees into his customers. The company also hired large numbers of immigrant workers, mostly Central, Eastern and Southern Europeans and to a lesser extent African Americans from the huge wave of the Great Migration during precisely the era of the Model T. Intense study of Ford’s wage structure and Sociology Department in Detroit, usually carried out at Universities in Michigan, offer a wide spectrum of the motives of Henry Ford and his company integrating Black and foreign personnel into the company and into industrial America. The situation in Cincinnati has not been examined as closely. Anecdotal evidence indicates at least some African Americans worked at the Walnut Hills plant, and at other Ford plants in later years. The Southwest quadrant of Walnut Hills also included many immigrants during the first half of the twentieth century, especially from Italy and Ireland. The company’s meticulous record-keeping undoubtedly could provide a fertile field for analysis of the sociology of workers in the Walnut Hills plant.

The Model T factory in our neighborhood operated only a about a decade longer than original vehicle. Ford continued to use the plant sporadically into the depression years of the 1930’s. Production ceased in 1938. The massive, open floor plan building the took on a new role as a distribution center for Sears and Roebuck farm equipment, just a few blocks from the company’s retail store at Lincoln and Reading Road. But that is a story of another generation’s business innovation.

References:

On the adaptation of the old Ford plant as an office building, see for example, Urban Land Instituted Development Case Studies Case No. C035001.

For a discussion of the economics of the carriage industry in Cincinnati in the late nineteenth century, see Edward P. Duggan’ “Machines, Markets, and Labor: The Carriage and Wagon Industry in Late-Nineteenth-Century Cincinnati,” The Business History Review, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Autumn, 1977), pp. 308-325. One of the main points of the article is the extent to which capitalization of the carriage industry involved general business expenses or “trade capital.”

For an overview of vehicle manufacture in Cincinnati, see Ohio Federal Writers’ Project, They built a city; 150 years of industrial Cincinnati, (Cincinnati Post, 1938), Chapter 9.

For a thumbnail history of Ford’s presence in Cincinnati see Mike Boyer. “Ford motored into Cincinnati long ago, Cincinnati Enquirer Sunday May 10, 1998.

On the introduction of the moving assembly line, with reference to moving pork “disassembly lines” in Cincinnati and Chicago, see Kurt Ernst, “Henry Ford’s moving automotive assembly line turns 100,” Hemmings Motor News October 7, 2013.

On the construction of branch Model T assembly plants, see Ford Times, v. 8 n. 9, available online with additional commentary at The Henry Ford Museum.

On construction and fitting-out of the Walnut Hills factory, see The Iron Age, Feb 11, 1915.

On the opening of the plant, see Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce, The Cincinnatian v 2 n. 14, April 5, 1915.

For an ad for “Walnut Hills … several good rooming houses on the West Hill, close to the new Ford Automobile plant.” See the Cincinnati Enquirer, 22 November 1914, p. 26.

On the Ford Sociology Department, see “Ford Sociological Department & English School,” The Henry Ford Museum.

Or for a less benign interpretation, Kat Eschner, “One Hundred and Three Years Ago Today, Henry Ford Introduced the Assembly Line: His Workers Hated It” Smithsonian.com December 1, 2016.