Cincinnati’s topography, with the original city in the river basin expanding to increasing elevations up the surrounding hills, presented a problem for the design of water supplies. The Queen City actually had a municipal water supply from the 1830’s, quite a progressive public service. The most basic principle of hydraulic engineering is that water flows down hill, but the Ohio River afforded the only source of water sufficient for a city with tens of thousands, indeed by the time the reservoir was finished, hundreds of thousands of occupants. The municipal supply therefore had to pump water up to a reservoir above the residents, in order for it to flow down into their houses and businesses. Before the Civil War that goal could be accomplished with an open stone tank on Third Street, at the base of Mt. Adams. The city’s expansion into the Over the Rhine neighborhood beginning in the 1850’s nearly reached the level of the reservoir. Moreover, with a capacity of 5 million gallons, the reservoir held less than a single day’s supply of water, leaving no room for failure of the pumps.

Cincinnati’s topography, with the original city in the river basin expanding to increasing elevations up the surrounding hills, presented a problem for the design of water supplies. The Queen City actually had a municipal water supply from the 1830’s, quite a progressive public service. The most basic principle of hydraulic engineering is that water flows down hill, but the Ohio River afforded the only source of water sufficient for a city with tens of thousands, indeed by the time the reservoir was finished, hundreds of thousands of occupants. The municipal supply therefore had to pump water up to a reservoir above the residents, in order for it to flow down into their houses and businesses. Before the Civil War that goal could be accomplished with an open stone tank on Third Street, at the base of Mt. Adams. The city’s expansion into the Over the Rhine neighborhood beginning in the 1850’s nearly reached the level of the reservoir. Moreover, with a capacity of 5 million gallons, the reservoir held less than a single day’s supply of water, leaving no room for failure of the pumps.

With the end of the Civil War in 1865, water distribution in Cincinnati reached crisis proportions. Flushed with victory, the whole of the North launched a public works extravaganza. Cincinnati rushed headlong into the frenzy. Nicolas Longworth’s Walnut Hills vineyard, which he called the Garden of Eden, had failed. A combination of grape blights, Civil War manpower requirements, and Longworth’s death in 1863 put an end to the production of Golden Wedding Champaign and Catawba Wines. The land was covered with brush and didn’t have any obvious useful purpose. Col. Adolphus Eberhardt Jones arranged for the city to purchase the Garden from the Longworth estate, setting aside a steep ravine as the site for a new reservoir (a counter-intuitive notion), and the rest of the property as a vast public park. The price of $3000 per acre represented the first of the bonus deals for Joseph Longworth, son, heir and executor of Nicolas Longworth. The site had one tremendous advantage for a Cincinnati reservoir: high above all developed and developing land in the river basin, water stored in the Garden of Eden would flow down, with tremendous pressure, to the whole city.

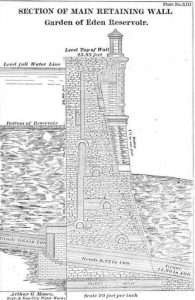

Joseph Earnshaw, Cincinnati City Engineer for a few years in the 1850’s, had later designed and supervised the construction of a water works for a large Union Army camp in Kentucky. He took charge of the Eden Park Reservoir in 1866, first opening a quarry at the east end of the Park. The reservoir was built in two sections, holding a total of a hundred million gallons of water. This design allowed for the draining of either section for maintenance and cleaning. Even standing next to the ruins of the lower wall for the reservoir it is difficult to comprehend the immensity of the project: “The wall is 48 ½ feet at the base and 120 feet in height. Its least width is 18 ½ feet … The extreme length of the wall is 1251 feet, and contains about 76,000 perches of stone.” (A perch is enough stone to lay a course a foot deep and a half a yard wide across a distance of one rod – fortunately, for our comprehension, just about a cubic yard.) Those 76,000 perches of stone came from a limestone hill above Kemper Lane. The abandoned quarry was later developed as the Twin Lakes Overlook, one of the most beloved features of Eden Park.

Joseph Earnshaw, Cincinnati City Engineer for a few years in the 1850’s, had later designed and supervised the construction of a water works for a large Union Army camp in Kentucky. He took charge of the Eden Park Reservoir in 1866, first opening a quarry at the east end of the Park. The reservoir was built in two sections, holding a total of a hundred million gallons of water. This design allowed for the draining of either section for maintenance and cleaning. Even standing next to the ruins of the lower wall for the reservoir it is difficult to comprehend the immensity of the project: “The wall is 48 ½ feet at the base and 120 feet in height. Its least width is 18 ½ feet … The extreme length of the wall is 1251 feet, and contains about 76,000 perches of stone.” (A perch is enough stone to lay a course a foot deep and a half a yard wide across a distance of one rod – fortunately, for our comprehension, just about a cubic yard.) Those 76,000 perches of stone came from a limestone hill above Kemper Lane. The abandoned quarry was later developed as the Twin Lakes Overlook, one of the most beloved features of Eden Park.

What is not visible at the ruins is the fact that the 120-foot high wall is mostly underground! To prevent it from sliding or toppling down the ravine, the engineers piled the back side of the wall with 50 feet of waste rock and earth as well as 75 feet of fill under the bottom of the reservoir. Before the backfill, the wall was not as high as the steeples going up on Walnut Hills Churches – but higher than their sanctuary roof lines. Beneath the wall the site was honeycombed with sewers between two and six feet across. The surface of the reservoirs covered about 14 acres with water twenty-five feet deep.

References:

For this series of articles on the Eden Park reservoir, the Cincinnati Water Works has an excellent historical section in its web site. See https://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/water/about/gcww-history/

The best contemporary sources are the annual reports of the water works. Most years they were published along with the reports of other city departments. The report for 1881 had an extensive history of the water works. It is available at https://books.google.com/books?id=8U4MAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r#v=onepage&q&f=false

The quote about the wall appears in 1881 report, p. 506; illustration appears as a plate between p. 508 and 509.

Many years from 1860-1911 are available from https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/012507855 and https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008374684

Others are on Google Books; see

1861 https://books.google.com/books?id=BEgMAQAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s and follow links at the bottom of the page for others

1868 https://books.google.com/books?id=BU0MAQAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s

1875 https://books.google.com/books?id=_E0MAQAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s

1877: https://books.google.com/books?id=7VIPAQAAMAAJ&source=gbs_similarbooks

A short history of the Eden Park Water Works appeared in Engineering News, April 23, 1881, p. 153 and 162 https://books.google.com/books?id=midKAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA162&lpg=PA162&dq=henry+earnshaw