In this photo taken August 10, 1928, Madison Road ended at DeSales Corner. From there westbound traffic flowed either north or southeast on Woodburn. (Only in Cincinnati does this geometry make sense.) This photograph captures St Francis DeSales Church (begun in 1872) on the right, the San Marco Apartments (1893) on the left. The row of buildings on the west side of Woodburn Avenue straight ahead had occupied the spot for decades and showed their backs to Walnut Hills. Woodburn Avenue had constituted the western boundary of the Village of Woodburn in the 1860s. A high-density strip just two or three blocks wide ran east of Woodburn Avenue from McMillan north to Gilbert Avenue, and was home to a German, mostly Catholic neighborhood. The road had served to separate the village from the city and continued to divide DeSales Corner from Walnut Hills.

DeSales Corner, like nearby Peebles Corner, anchored a streetcar suburb. Eighteen flats were listed in the white building on Woodburn at the left; dozens more lined filled buildings with names like the Krug on both sides of the street to the south east, the seven-story San Marco was the largest. (The oversized streetcar in the postcard, with power poles soar above the second story, was superimposed.) Each had retail on the ground floor and apartments above. Fenton’s narrow dry-cleaning shop at the base of the four-story building at the center of the photo is flanked by a stand-alone two-story building to the right and a wide three-story structure on the left. The building to the right had one storefront called the Economy Market and another selling Oysters and Poultry. The poultry could be bought either live or dressed; a detailed map of the area even indicated the “Chicken Killing” spot around back. The storefront to the left of Fenton’s, sporting an awning, was a liquor store; the Kroger Grocery next to it advertised that some Taft or other was running for Prosecutor. The leaded glass above the grocery display windows is still recognizable in that building today.

DeSales Corner, like nearby Peebles Corner, anchored a streetcar suburb. Eighteen flats were listed in the white building on Woodburn at the left; dozens more lined filled buildings with names like the Krug on both sides of the street to the south east, the seven-story San Marco was the largest. (The oversized streetcar in the postcard, with power poles soar above the second story, was superimposed.) Each had retail on the ground floor and apartments above. Fenton’s narrow dry-cleaning shop at the base of the four-story building at the center of the photo is flanked by a stand-alone two-story building to the right and a wide three-story structure on the left. The building to the right had one storefront called the Economy Market and another selling Oysters and Poultry. The poultry could be bought either live or dressed; a detailed map of the area even indicated the “Chicken Killing” spot around back. The storefront to the left of Fenton’s, sporting an awning, was a liquor store; the Kroger Grocery next to it advertised that some Taft or other was running for Prosecutor. The leaded glass above the grocery display windows is still recognizable in that building today.

The streetcar tracks with their intricate crossings run down the middle of Madison Road and both directions on Woodburn. Paris of wires hanging at about the top of the first stories, suspended from stay wires by electrical insulators, carried electric power; poles from the cars connected them to this grid. This spider-web, with bulbous insulators like cocooned insects, traced out the pattern of the tracks wherever the streetcars ran. It is significant that the tracks and the cables are in the middle of the streets; other traffic moved along the curbs, an arrangement that made more sense at horse-drawn speeds than automotive. Passengers entered and exited the streetcars using sidewalk like platforms between the tracks and the vehicular traffic lanes. These platforms, like the one in front of the church, had a substantial barrier marked with a hexagonal warning sign which came to be a significant traffic hazard for automobiles as well as protection for passengers and for the special streetlights that illuminated the stops at night. Yet the isolated traffic lane exposed the passengers to oncoming vehicles.

The transition from horse-drawn vehicles to faster, heavier trucks and motorcars was not in all ways a smooth one. Already in 1928 automotive parking further clogged the streets. A billboard spanning both the Kroger and the liquor stores advertised a bigger and better Chevrolet, presaging things to come.

This August 22, 1929 photograph of DeSales Corner from Madison Road captures the transition of Walnut Hills from a residential streetcar suburb to a throughway in an automotive culture dreamt of during the roaring twenties. The Great Depression and then the Second World War paused that transition for nearly two decades. Yet a careful examination of the photo speaks volumes about the vision of and for Walnut Hills just a couple of months before Black Friday.

The city knocked down three buildings on the west side of Woodburn to extend Madison Road into Walnut Hills. Gone was the nineteenth-century distinction between the German neighborhood around St Francis DeSales Church and the Black neighborhood anchored by the ten-year-new Frederick Douglass School in the distance. With its twin square towers a few blocks away on Alms Place, Douglass occupied the site of the Walnut Hills Colored School that dated back to 1870 to serve the children of the largely middle-class African American community. Apart from a white man in short sleeves sitting on the steps of St Francis, just about everyone racially identifiable in the photo was African American, all the adults with long sleeves and a couple of the men in suits.

The continuing evidence of streetcars is even more visible in 1929 than a year earlier. In both directions Woodburn, and east on Madison, the overhead power cables are more visible against the empty sky than they had been against the buildings the previous year. But note that no new wires or tracks went west: the broad Madison Road Extension was meant only for automotive traffic. The last section of Victory Parkway, between McMillan Street and Lincoln Avenue, was also constructed in 1928/29. The parkways suggested around the turn of the century as broad greenways for private carriages morphed into automotive highways. Victory Parkway provided a north south through street, much more convenient for commuters than Gilbert Avenue with its high concentration of streetcar and commercial traffic. The wide Madison Road Extension emerging from DeSales corner, carried automotive traffic only as far as the Parkway. The cars in this photo were necessarily hurrying to or from somewhere else, since there was nothing yet open along the street.

In 1929, other changes were in the air. On opposite sides of the new stretch of Madison we see the construction of self-consciously modern (even Moderne) buildings. To the left is the wonderful Art Deco Central Trust Bank building, still awaiting its roof and the massive green marble door frame. Clad in limestone, streamlined in its sweep around the corner, wedged into the triangular lot created by Madison Road’s exit from the intersection at another obtuse angle, the bank was as horizontal as its predecessor was vertical. Across Madison is a more work-a-day version of a single-story structure likewise wrapped around the corner, a row of simple storefronts with minimal stone or cast concrete decoration embedded in red brick. The corner store is now gone, but part of the brick row to the west remains. The motorist had no need for the high-density design placing apartments compactly above storefronts: a home with a yard in Hyde Park was within an easy commute of the stores on Woodburn, and those at Peebles Corner as well.

Madison Road Extension from the West, 1928-1929

The Madison Road Extension ran west from Woodburn Avenue at DeSales corner. The corner lost three buildings, but immediately saw attractive new development to soften the gap. Yet from the west, from Walnut Hills, the project had considerably greater impact.

A series of three photos of the construction of the Madison Road Extension from the Walnut Hills side tells the story.

A series of three photos of the construction of the Madison Road Extension from the Walnut Hills side tells the story.

In August 1928 we see St Francis DeSales church behind a modest brick house about as close to rural life as possible in a big city.

By the next March, the roadbed was cut through, an embankment shielding white Walnut Hills and the old Woodburn neighborhood to the south and east (on the right in the picture) from the African American neighborhood to the northwest. The roadbed was not complete, and the new buildings at DeSales Corner had not been started; this moment provided the best portrait of St Francis DeSales Church and the San Marcos Apartments facing each other across Madison.

By the next March, the roadbed was cut through, an embankment shielding white Walnut Hills and the old Woodburn neighborhood to the south and east (on the right in the picture) from the African American neighborhood to the northwest. The roadbed was not complete, and the new buildings at DeSales Corner had not been started; this moment provided the best portrait of St Francis DeSales Church and the San Marcos Apartments facing each other across Madison.

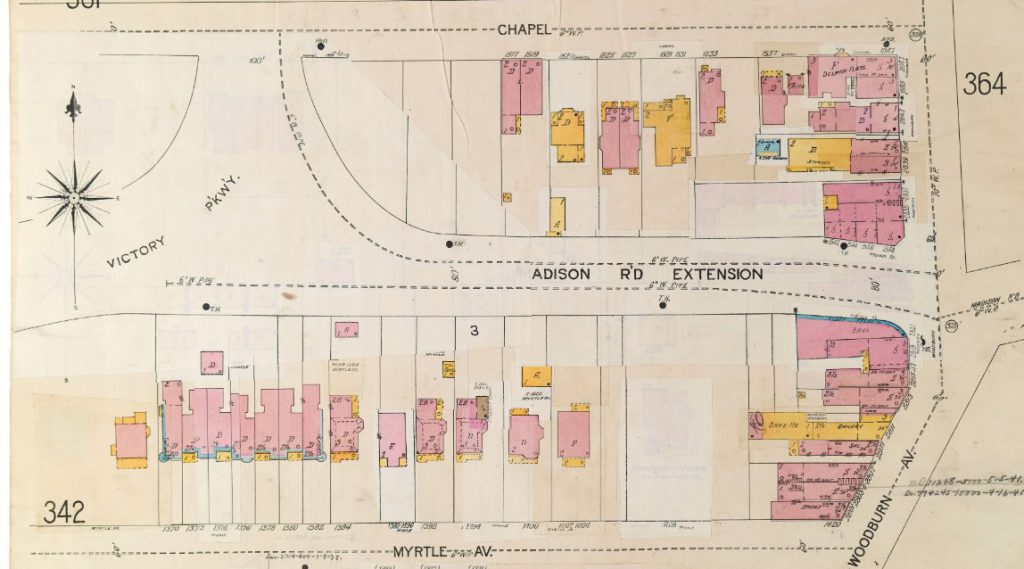

By October 1929, the completed Madison Road Extension joined the new Victory Parkway in a vast triangular swath of asphalt. The detailed map, with the original layer bleeding through, showed that the road pasted over existing buildings lost without replacement both in the path of the extension, and on Chapel Street where it joined Victory Parkway. The road itself was much more terrifying than its image on the map.

By October 1929, the completed Madison Road Extension joined the new Victory Parkway in a vast triangular swath of asphalt. The detailed map, with the original layer bleeding through, showed that the road pasted over existing buildings lost without replacement both in the path of the extension, and on Chapel Street where it joined Victory Parkway. The road itself was much more terrifying than its image on the map.

The high speed automotive route created a dangerous barrier between neighbors in what immediately came to be called “East Walnut Hills” (east, that is, of Victory Parkway) and Walnut Hills proper. A block to the north and one to the west of Victory Parkway sat Frederick Douglass School on Alms Place, the heart of the Black community. Within a block Bethel Baptist Church and Brown Chapel AME served thriving Black congregations. The segregated Black Gordon Terrace Apartments on Ashland at Chapel were even closer to the Madison Road-Victory Parkway intersection, which clipped a corner off the Ashland Park across the street from the Gordon.

Symbolically as well as physically, the new auto routes separated Douglass from the old Walnut Hills High School at Ashland and Burdett. A decade earlier, DeHart Hubbard had made his way from Douglass to Walnut Hills High School in the 1910s, a track champion in both the Black and the white school, and then on to the University of Michigan and Olympic Gold in 1924. His white Walnut Hills football team mates in 1916 had refused to play without him. The construction of the new, high speed automotive highways brutally disrupted that short migration. Generations of school children, long after both sides of the Parkway became predominantly Black, had to venture across that traffic-control nightmare to find their way to Douglass, Hoffman and Burdett Elementary, the repurposed High School building.