Archibald Dickerson and the Walnut Hills Pharmacy, 1919-1924

We have seen that African American pharmacist Archibald Dickerson opened the Walnut Hills Pharmacy at 1126 Chapel Street, across the street from Frederick Douglass School, in 1908. The store flourished, and Dickerson found a place as a leader in the Black community in Walnut Hills during the 1910s. During WW I he volunteered for the military only to be mustered out after a few months, although he continued patriotic support for the war.

Dickerson’s boldest civil rights role came just after the war in November 1919 – at the end of a season of white American attacks on Blacks known as the Red Summer. Cincinnati is notable for avoiding any large-scale violence at the time. Yet we had our own small incident in Walnut Hills. Arabella Kirkpatrick, a thirteen-year-old student at Douglass School, worked as a babysitter. She went to a white family’s house one evening in Hyde Park, but the white parents did not drive her home as promised. Her frantic mother discovered the next day that the employers had accused her of stealing, “punished” her, and had her arrested. Arabella ended up in the hospital; Dickerson’s business partner Dr. Norval Vaughan was denied access to examine and treat her.

Dickerson’s boldest civil rights role came just after the war in November 1919 – at the end of a season of white American attacks on Blacks known as the Red Summer. Cincinnati is notable for avoiding any large-scale violence at the time. Yet we had our own small incident in Walnut Hills. Arabella Kirkpatrick, a thirteen-year-old student at Douglass School, worked as a babysitter. She went to a white family’s house one evening in Hyde Park, but the white parents did not drive her home as promised. Her frantic mother discovered the next day that the employers had accused her of stealing, “punished” her, and had her arrested. Arabella ended up in the hospital; Dickerson’s business partner Dr. Norval Vaughan was denied access to examine and treat her.

Dr. Dickerson was among five Walnut Hills Black men who called a meeting to protest the treatment of the girl and her mother. The trail of Arabella’s story seems lost, perhaps indicative of the lack of recourse in the Black community for white abuse. Given the pharmacist’s clear support for Black participation in the War, his activism was of apiece with that of returning Black veterans often the targets of Red Summer riots, especially in the rural South. Yet in the depths of the Jim Crow era, Archibald Dickerson stood beside her – and Wendell Dabney’s Black weekly, The Union, stood by Dickerson.

Even in the shadow of his desperate defense of this most vulnerable person in his community, Archibald Dickerson and his drug store apparently thrived. In 1920 he was ready to move the family from the rented apartment behind the store on Chapel Street. If we were to ask our usual question, what did success look like for this professional business owner in his late thirties, it would seem that it looked like the single-family house valued at $4500 on Bramble Avenue at Azalea, in Madisonville, that Dickerson purchased in March 1920.

In 1922, Dickerson was also able to move his store a few doors east to 1200 Chapel, on the other side of Alms Place, into a grand old building, the Devote, which had been purchased by Horace Sudduth’s Walnut Hills Enterprise Company. (A few years later, the building and pharmacy both took the name Peerless.) Again, if we ask what did success look like, we might say that after 12 years it looked like moving from an improvised storefront into a larger space in a more prestigious commercial building. Dickerson had turned the former wall-paper hanger’s establishment into an attractive retail address: after he moved out of 1126 Chapel, a branch of the A & P grocery moved in!

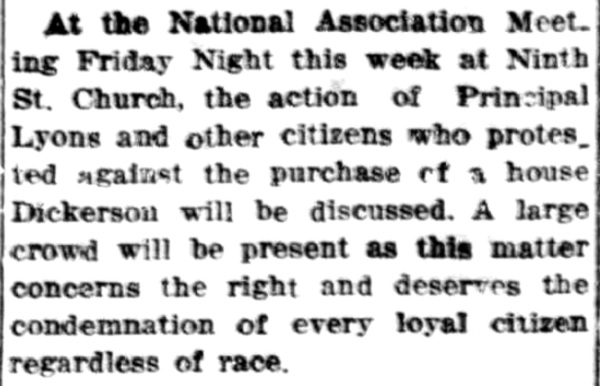

But the Dickerson’s success would be fleeting. In the language of the day, the family had tried to cross the “color line” in Cincinnati, moving into a home unofficially reserved for whites. There was a long-standing Black community in Madisonville. It seems that the house on Bramble was outside of it: Dickerson “and his family had moved into a house which adjoins the homes of white persons.” Memories of Dickerson’s defense of the young Black babysitter may have escalated the situation. In early April 1920, two hundred white citizens gathered for an “indignation meeting” concerning the sale “of properties to Negros in the residential district of Madisonville.” They met in the suburb’s Odd Fellows Hall. The principal of the new East High School (later renamed Withrow High School) presided over the protest. Yet the white community was unable to reverse the sale once it had happened and the Black family stayed. Again Dabney, an ardent integrationist, took Dickerson’s side, editorializing that the segregationist participation of the white high school principal should disqualify him from his position.

But the Dickerson’s success would be fleeting. In the language of the day, the family had tried to cross the “color line” in Cincinnati, moving into a home unofficially reserved for whites. There was a long-standing Black community in Madisonville. It seems that the house on Bramble was outside of it: Dickerson “and his family had moved into a house which adjoins the homes of white persons.” Memories of Dickerson’s defense of the young Black babysitter may have escalated the situation. In early April 1920, two hundred white citizens gathered for an “indignation meeting” concerning the sale “of properties to Negros in the residential district of Madisonville.” They met in the suburb’s Odd Fellows Hall. The principal of the new East High School (later renamed Withrow High School) presided over the protest. Yet the white community was unable to reverse the sale once it had happened and the Black family stayed. Again Dabney, an ardent integrationist, took Dickerson’s side, editorializing that the segregationist participation of the white high school principal should disqualify him from his position.

A more violent attack followed. In January 1921, the (white) Cincinnati Commercial Tribune reported, “making an appearance after a short rest, the ‘window smasher’ shoved the glass out of a rear door in the home of Archibald Dickerson … last night and stole two savings banks containing $20. He [the smasher] ransacked the lower floor of the house, but took nothing else.” The escapades of the window smasher indeed appeared regularly in the news around that time, but Madisonville was outside the usual range of his crimes. It is impossible to know whether the break-in was really part of the spree, or whether it came as an escalation of the indignation expressed by the white community the previous year.

The harassment moved from the extralegal to the legal. There was a series of lawsuits from a real estate agent, beginning in 1922, for an amount less than $100. This was followed by liens and suits again for small amounts. Such were the micro-aggressions of the day. Dickerson finally lost his house in a Sheriff’s Sale in 1924, owing to the compounding judgements in favor of his realtor. He lost his business as well. When he withdrew from the Walnut Hills Pharmacy in May 1924, a brief mention in the Chicago Defender explained Archibald Dickerson “has retired on account of ill health.”

It seems likely that the collapse of Dickerson’s health, mental or physical, was owing primarily to the growing racism manifested in the Red Summer of 1919 or the Tulsa race massacre a hundred and one years ago today. It robbed him of his property, his business, and his place in his community. Wendell Dabney sometimes took a dislike to his fellow “Race Men,” especially when he saw them as weak. A staunch supporter during Dickerson’s patriotic travails during the World War and in the courageous Civil Rights stand in 1919, Dabney failed to mention Dickerson in his 1926 Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens.

– Geoff Sutton