In 1891, Frederick Alms built a large apartment building on McMillan, just across Elmwood Place (later renamed Alms Place, now Victory Parkway) from his palatial home. He intended the place as a residence for families who “could have the fine air of a hill-top.” The new property also shared with his residence the magnificent view down the ravine (since filled in by Victory Parkway), beyond Francis Lane and past the Emery mansion Edgecliff to the Kentucky hills in the distance. To my eye, the Samuel Hannaford designed hotel provides architectural cues echoed in the Frederick Douglass School erected a few blocks north in 1911 to replace the Elms Street Colored School.

In 1891, Frederick Alms built a large apartment building on McMillan, just across Elmwood Place (later renamed Alms Place, now Victory Parkway) from his palatial home. He intended the place as a residence for families who “could have the fine air of a hill-top.” The new property also shared with his residence the magnificent view down the ravine (since filled in by Victory Parkway), beyond Francis Lane and past the Emery mansion Edgecliff to the Kentucky hills in the distance. To my eye, the Samuel Hannaford designed hotel provides architectural cues echoed in the Frederick Douglass School erected a few blocks north in 1911 to replace the Elms Street Colored School.

Alms spent $400,000 to build and furnish the building to accommodate hundreds of guests. “The suites of rooms are large, and homelike, and beautiful. The parlors and reception-rooms are elegant and yet homelike. The appointments throughout are just what the most refined people would desire in their own homes. The dining-rooms are spacious, but light, handsome and attractive. Mr. Alms was very much interested in the furnishings; so we find carpets, rugs, draperies, furniture, porcelain, silverware and all other furnishings, elegant and of exquisite taste. … He did not forget the table, and wished his guests to have one of the finest cuisines in this country. He was even as anxious that his guests should have fresh eggs, milk, cream and butter, direct from the finest dairies in the country, as he was for his own table at his home. When he was in Colombo, Ceylon, he ascertained the very best tea which could be had in the whole Orient, and he had this tea imported for his hotel, and to-day the guests are served with this luxury.”

In about 1894 Frederick Alms styled the building as the Hotel Alms. The distinctions among apartments with services, residential hotels, and what were then called “transient” hotels for short-term visitors were considerably more fluid at the time than they are today. The Alms seems always to have filled all three roles, serving as a permanent address for some residents. Indeed, after Frederick’s death in 1898, Mrs. Alms took a fantastic apartment in the hotel. It also played many of the other roles usually associated with the large downtown hotels – banquet facilities and meeting rooms accommodated large local events including, on occasions, fundraisers hosted by the proprietor for favorite charities.

The Alms thrived as a hotel, but was soon surpassed in the apartment market. The early years of the twentieth century saw the construction of many nearby luxury apartments, complete with servants’ quarters in their attics. The Verona around the corner on Park, the Clermont a few blocks east on McMillan, both built in 1906, and the 1904 Alexandra at Gilbert and what is now William Howard Taft, all provided attractive permanent apartments for well-to-do in the popular suburb.

For almost 35 years after the original Hotel Alms went up in 1891, the physical plant grew in regular, substantial increments. Indeed, expansion plans proliferated at a such a rate that a couple of major additions got to the point of architectural drawings but gave way to alternative and more elegant construction. The Sanborn Fire Insurance maps for the year in which the hotel was first constructed show a block of 14 townhouses or apartments on McMillan just west of the Alms, with the note “To be Built.” This was certainly not the only false prophesy of optimistic developers. Early photographs of the hotel all show a low pavilion in that spot; behind it, there was a covered octagonal ball room on a raised platform.

By 1904, the Sanford maps show a second, four-story building set back from the side street, by that time renamed Alms Place in honor of the deceased Frederick Alms. The ground floor comprised dining rooms; above there were new hotel rooms. The setback was accomplished with a slightly raised terrace, build atop a basement pump room. The remainder of the basement bristled with modern machinery and fireproof construction – a room full of “generators and dynamos,” a “freezing tank,” a boiler room with an asbestos lined ceiling and an oven room with an iron ceiling. A low service building behind the addition, wrapping around the ballroom, housed the kitchen, an ample wine cellar, and a “steam laundry and dry room;” that is, industrial washing machines powered by a small steam engine. The ballroom communicated with both the hotel buildings by way of halls labelled “wired glass roof” – skylights by day and electrically illuminated glass hallways by night.

Sometime around the early 1920’s, the Samuel Hannaford and Sons architectural firm drew up plans for a nine-story addition, wedged in on McMillan Street, right up to the sidewalk and dwarfing the original 1891 building, on the part of the lot occupied for a quarter-century by the ballroom. The plan would have changed the character of the hotel from the original airy suburban feel to a more crowded urban setting consonant with Peebles Corner a few blocks to the west. The long-proposed construction of Victory Parkway along the route of Alms Place, it seems, derailed the Hannaford design. Initially envisioned as a broad park-like boulevard for walking and horse-drawn carriages, by the time the last section through Walnut Hills went in in 1929 it had become a tree-lined automobile route faster-moving than the existing main roads which were clogged with public streetcars. The construction would widen the block of Alms Place between McMillan and Locust (now William Howard Taft Road), removing the Alms mansion and most of the other buildings across the street, making it a more attractive and elegant road than McMillan. Half a block to the north, Victory Parkway would branch off to the northeast, connecting with Madison Road and the already-completed Parkway to the north.

Anticipating this road project, in 1925, the Alms Hotel built a new nine-story building facing the Parkway at the north end of the block, at the intersection of Victory and Locust. The hotel acquired the whole north end of the block, between Alms Place and Park Avenue, allowing a comfortable setback from Victory and a courtyard between the wings of the new structure. Around the corner on Locust, filling out the block, the Hotel erected a thoroughly modern four-story parking garage with space for 400 cars. Services like laundry moved into the new building, the old service building was torn down to make way for a large garden with al fresco dining between the old ballroom on McMillan and the new buildings on Locust.

Anticipating this road project, in 1925, the Alms Hotel built a new nine-story building facing the Parkway at the north end of the block, at the intersection of Victory and Locust. The hotel acquired the whole north end of the block, between Alms Place and Park Avenue, allowing a comfortable setback from Victory and a courtyard between the wings of the new structure. Around the corner on Locust, filling out the block, the Hotel erected a thoroughly modern four-story parking garage with space for 400 cars. Services like laundry moved into the new building, the old service building was torn down to make way for a large garden with al fresco dining between the old ballroom on McMillan and the new buildings on Locust.

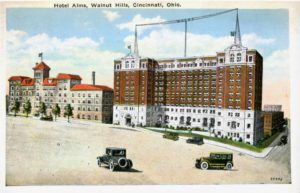

A contemporary postcard, with an imaginary overly wide Victory Parkway including sketched-in automobiles (some farther out of scale than others), captures the sense of roaring twenties modernity.