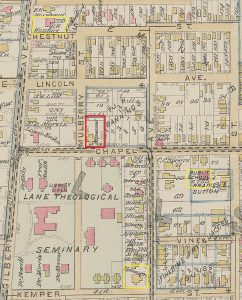

The one-time Manse Hotel building at 1004 Chapel Street, originally a cruciform (cross shaped) frame (wood) home constructed in about 1876, was the first house on north side of its Chapel Street block at Monfort, in this map labeled (and misspelled) “Mulbery.” In the 1884 cadastral (tax) map, the Chapel Street house is labeled “Hayward” for the tax payer. The map highlights the lot and building in a red box. For reference in the neighborhood, several other buildings appear in yellow boxes. From the top left, at Gilbert and Foraker (then Chestnut), the Elms Street Colored School south of Chapel on the right, and near the bottom, north of Kemper, the house in the first photograph like the future Manse a frame house with a Mansard roof. Note that in all the detailed maps frame construction is indicated by yellow shading while brick or stone structures are shaded pink.

The one-time Manse Hotel building at 1004 Chapel Street, originally a cruciform (cross shaped) frame (wood) home constructed in about 1876, was the first house on north side of its Chapel Street block at Monfort, in this map labeled (and misspelled) “Mulbery.” In the 1884 cadastral (tax) map, the Chapel Street house is labeled “Hayward” for the tax payer. The map highlights the lot and building in a red box. For reference in the neighborhood, several other buildings appear in yellow boxes. From the top left, at Gilbert and Foraker (then Chestnut), the Elms Street Colored School south of Chapel on the right, and near the bottom, north of Kemper, the house in the first photograph like the future Manse a frame house with a Mansard roof. Note that in all the detailed maps frame construction is indicated by yellow shading while brick or stone structures are shaded pink.

It seems the Hayward house was an architecturally typical “Second Empire” house, which means in the Cincinnati context little more than it had two full stories plus a third under a “Mansard Roof.” This requires a first significant digression about architectural styles. In Paris, during the Second Empire of Napoleon III during the 1850s and ‘60s, building codes did not count an attic as part of a building’s height. Developers therefore built floors one or even two stories above code with a nearly flat hipped roof, and slightly sloping walls. In Paris, the not quite vertical exterior walls were clad in roofing slate and said to be the steeper slope of the hipped roof above. They formed completely habitable living space that counted as an attic, winked at by the building inspectors. The Parisian “roof” walls were called “Mansard” rooves, to supply a dubious connection to a rather different historical architectural style in order to add a veneer of plausibility to the code-inspired architectural feature. Being French, the style was embraced in the US without the necessary legal mother of that invention, although in 1916 New York imposed its own codes encouraging Mansard construction. I have found no pictures of the original building, but the first photo shows another frame house highlighted in the bottom yellow box and still standing at Park and Yale (then Kemper Street) just a few blocks away, with its slate-clad third floor.

It seems the Hayward house was an architecturally typical “Second Empire” house, which means in the Cincinnati context little more than it had two full stories plus a third under a “Mansard Roof.” This requires a first significant digression about architectural styles. In Paris, during the Second Empire of Napoleon III during the 1850s and ‘60s, building codes did not count an attic as part of a building’s height. Developers therefore built floors one or even two stories above code with a nearly flat hipped roof, and slightly sloping walls. In Paris, the not quite vertical exterior walls were clad in roofing slate and said to be the steeper slope of the hipped roof above. They formed completely habitable living space that counted as an attic, winked at by the building inspectors. The Parisian “roof” walls were called “Mansard” rooves, to supply a dubious connection to a rather different historical architectural style in order to add a veneer of plausibility to the code-inspired architectural feature. Being French, the style was embraced in the US without the necessary legal mother of that invention, although in 1916 New York imposed its own codes encouraging Mansard construction. I have found no pictures of the original building, but the first photo shows another frame house highlighted in the bottom yellow box and still standing at Park and Yale (then Kemper Street) just a few blocks away, with its slate-clad third floor.

Several families occupied the Chapel Street residence in the late 1870s. An 1884 cadastral (tax) map, which showed the owner as “Hayward”, delineates the cross-shaped footprint. Albert Hayward supervised the telegraph operations of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad; he first appeared in city directories with a home address at the “n. e. c. Chapel and Beech, Walnut Hills” – the north east corner of Chapel and Beech – in 1882. (To add to the confusion, Beech was actually a name of the street south the Lane Seminary campus; a connecting path through the campus remained nameless; Mulberry was the name of the continued street north of the campus. It seems the compiler of the directory did not get all the memos. Thankfully, Mulberry was renamed Monfort for its most prominent family residing in the Beecher-Stowe house at Beech and Foraker – with Monforts remaining, like Haywards, for multiple generations into the twentieth century.) Albert Hayward’s son, who went by the initials A. W., at first appeared in directories as an assistant engineer for the O&M RR (his father’s business). Beginning in 1885, however, A. W. listed himself as an architect. He had a large, mostly residential practice in Walnut Hills in the firm Des Jardins and Hayward. The pair generally worked in brick. The second partner did not hesitate to practice on his own frame residence on Chapel – a material easier to modify with exuberant balloon construction. By 1891, his (or his father’s) home had sprouted a semi-hexagonal, three-window bay with full Mansard treatment to the left. This bay, jutting from between the Chapel Street front and the original semi- transept – the cross member on the plan of that side of the cross – created a (to my eyes rather awkward) void between the addition and the original semi-transept.

To the right, Hayward attached a wing to the Chapel Street side connected to front of the other semi-transept. This one was capped with a decorative porch on the third floor, breaking the Mansard convention. A rectangular bump-out on this addition was flush with the original Chapel Street wall (the top of the cross), leaving another puzzling void in the front façade. A square tower in the midst of the mansard roof may have been part of the original design – it would not be completely out of second empire character in the 1870s – or it may have been another bit of Hayward’s fussing. All these modifications, which may have been made at different times, are on the front facing Chapel Street; they turned the original rather formal presentation into a sort of rambling, eclectic Victorian. A small addition at the rear probably provided kitchen space.

The Hayward home, rather like Walnut Hills itself, grew by accretion. Just as architecture in Walnut Hills includes examples of every decade’s fashions since the 1930s, this single building included many fashions reflective of the tastes and the construction techniques of its century-long history. We must not take this eclecticism as some sort of contamination, but rather as ongoing embellishment. It was a fashionable, home of the 1890s as much as it had been a fashionable, modern home of the 1860s. (Many early Walnut Hills homes designed by James Keys Wilson – the Baker Place on Baker Place or the Keys place on Keys Crescent – were originally build with wings and towers in different style to provide the illusion of accretion over the ages, but that is a matter beyond the scope of even this analysis.) We must also note that the original large Hayward place had grown to a mansion of seventeen rooms, and sometimes housed more than one generation of Haywards. As with other grand houses of the neighborhood – the Beecher-Stowe house a block north of Foraker or the Burroughs residence next door at 1010 Chapel – 1004 Chapel adapted to a new and changing neighborhood in the 1910s.