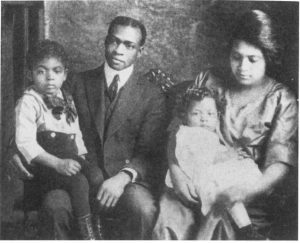

James Robinson and his family in Cincinnati

James Robinson was born in Sharpsburg, Kentucky in 1887. He attended Fisk University, one of the premier Historically Black Colleges, founded in Nashville Tennessee in 1866. Robinson graduated from Fisk in 1911. He then enrolled at Yale University. He spent a year completing a second bachelor’s degree in 1912 and began to study sociology in graduate school. He got his master’s for Yale in 1914 and embarked on a Ph. D. He spent the 1914-15 academic year at Columbia.

In 1915, Robinson moved to Cincinnati to teach at Frederick Douglass School and to pursue further research. We can get some idea of the status of the Colored School in Walnut Hills when we realize that one of the best-educated young men of his generation, on either side of the color-line, came to teach here. His research, we shall see, earned the respect of a large segment of the teachers in the Cincinnati Public Schools.

Before turning to Robinson’s work, we need to take a brief excursion through the history of American Sociology. That history is a study in racial politics. WEB DuBois, the most brilliant African American intellectual of the first half of the twentieth century, founded the discipline of sociology in this country. A series of essays DuBois wrote in the 1890’s and collected in The Souls of Black Folk in 1903 set out the fundamental principles of social analysis of “the problem of the color-line.” A New Englander descended from free Blacks in the North, DuBois had graduated from Fisk in 1888, and received a second bachelor’s from Harvard in 1890. After graduation DuBois won a fellowship in Germany where he studied with the founders of the European sociology, including Max Weber. Denied a renewal of his fellowship (and the opportunity to finish his German Ph. D.) DuBois returned to Harvard. He wrote a dissertation in history detailing federal legislative battles over the importation of slaves into the US after importation became illegal – a sure indication that the law did little to stop the trade. His 1895 Harvard Ph. D. came as a sort of consolation prize for the missed opportunity in Germany.

After Harvard, DuBois came to Ohio for a year to teach at the Historically Black Wilberforce College. He moved to the University of Pennsylvania and a meager fellowship where he single-handedly interviewed thousands of residents of one of the African American wards in Philadelphia. His Philadelphia Negro published in 1899 set the standard for field work and statistics in sociology. DuBois then assumed a professorship at the Historically Black Atlanta University, now affiliated with Morehouse and Spellman Colleges. He held a conference each year on significant issues facing American Negros and edited a series of ten annual volumes based on his own research and on the proceedings of the conferences. While at Atlanta DuBois prepared a long essay on race, in German, which Max Weber published in his influential journal. Weber wrote in 1910, “the most important sociological scholar anywhere in the southern states in America, with whom no white scholar can compare, is a Negro – Burckhardt DuBois.” DuBois accomplished all this before he turned to activist journalism as the editor of the NAACP magazine The Crisis in 1910.

James Robinson became a leading sociologist in the Atlanta tradition. In Cincinnati he carried out a real-time study of the Great Migration of African Americans in the South to the cities of the North. Robinson worked with the leaders of the city’s African American community to develop his plans. He also enlisted “every conductor on the four southern railroads converging here” to keep a record of “the migrants from the South destined for this city.” Volunteers reinforced paid assistants in a “house-to-house” investigation like DuBois’s research in Philadelphia twenty years earlier. Moreover, Robinson reported, “three hundred and fifty-seven teachers in the public schools made twenty thousand telephone interviews.” This was what we might call big data in the 1910’s, all tabulated by hand.

Robinson presented his work at the National Conference of Social Work in July 1919. His report, “Revelations of the Cincinnati Negro Survey,” was worthy of the DuBois school. Data driven and thorough, it offered a comprehensive analysis of its subject.

Like DuBois, James Robinson took a detour from the academic world to do policy development and advocacy. He became the Executive Secretary of the Negro Civic Welfare Committee of Cincinnati’s Council of Social Agencies. The solutions he proposed for Cincinnati (in line with his employment at Douglass) advocated the organization and support of institutions within the Negro community. He especially hoped to enlist the organized support of the Churches in the community – not, he emphasized, seeking religious or theological solidarity, but coordinating the provision of Social Services through 53 Church Auxiliaries. He sought the support and development of a Black-run YMCA and YWCA, of the Colored Orphan Asylum, The Crawford Old Men’s Home and a home for Aged Colored Women. His intricate diagram of social support networks included boxes for the Walnut Hills Day Nursery and for “35 clubs” – perhaps the women’s service organizations in the Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. All these organizations had active supporters and organizers on the Frederick Douglass School faculty.

Like DuBois, James Robinson took a detour from the academic world to do policy development and advocacy. He became the Executive Secretary of the Negro Civic Welfare Committee of Cincinnati’s Council of Social Agencies. The solutions he proposed for Cincinnati (in line with his employment at Douglass) advocated the organization and support of institutions within the Negro community. He especially hoped to enlist the organized support of the Churches in the community – not, he emphasized, seeking religious or theological solidarity, but coordinating the provision of Social Services through 53 Church Auxiliaries. He sought the support and development of a Black-run YMCA and YWCA, of the Colored Orphan Asylum, The Crawford Old Men’s Home and a home for Aged Colored Women. His intricate diagram of social support networks included boxes for the Walnut Hills Day Nursery and for “35 clubs” – perhaps the women’s service organizations in the Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. All these organizations had active supporters and organizers on the Frederick Douglass School faculty.

These efforts did not go unnoticed. In 1924 George E. Haynes, the highest ranking African American in the federal Labor Department, observed:

“Perhaps the most fully worked out and best piece of social engineering in race relations in a northern community has been developed during the past six years in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the inter-racial work of the Council of Social Agencies, with James H. Robinson as executive secretary. They have coordinated the Negro churches, fraternal bodies, women’s clubs, Y. M. C. A. and Y. W. C. A. with the white social agencies and organizations. The Negro population increased from about 20,000 to 35,000 in ten years, largely during the 1916-18 migration. These people have been integrated into the city’s life through their leaders and organizations to an extent which hardly seemed workable ten years ago.”

Robinson remained in Cincinnati through 1928. His Negro Civic Welfare Association, in conjunction with other organizations, established the Shoemaker Clinic to provide free medical services in the West End to poor African Americans.

In 1929 Robinson moved back to Fisk University as a professor and as the supervisor of Negro Welfare in Tennessee. There he conducted another major sociological study for which he earned his Ph. D. in 1934; Yale University Press published it as A Social History of the Negro in Memphis and in Shelby County. Finally credentialed, Dr. Robinson returned to Ohio in 1933 as a professor of sociology and social administration at Wilberforce University, where he served as the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts from 1939-1949.

In 1920, a few years after he left Frederick Douglass School, James Robinson wrote a sort of testimonial for the school that appeared in a booklet commemorating the tenth anniversary of the second Frederick Douglass School building:

“Douglass School is a happy combination of beauty and service. There are few buildings in the country which serve so many colored children and surpass it in grandeur. Its imposing presence is in itself a feature of importance for it is a source of pride to the community and an inspiring example for less progressive parts of the country where the youth is taught in buildings inadequate for the purpose.

“Walnut Hills, the section from which most of its pupils come, is one of the largest of the several communities in which the colored people of the city live. It is an old settlement and has been the scene of events which made history. The school is as inseparably linked with the life of the community of the past as with its problems of today.

“It is a progressive settlement and gives evidence of thrift and even affluence not generally known to exist. Statistics show a low death rate, a low criminal rate and a large percentage of home owners. Many of these homes are not only comfortable but beautiful and reflect a healthy and wholesome family life. The Hill is comparatively free from the unsanitary conditions generally concomitant with tenement life in large cities.

“Not only do children of the normal type attend the school, but the anemic, the defective and the retarded are given a chance to fit themselves for the battles or life which are all the fiercer for them because of their handicaps. The library, evening schools and community meetings afford opportunity for the older people to improve themselves and to give free play to ideas and instincts which would otherwise stifle and die for want of expression. Certainly the colored section and the larger cosmopolitan area owe much to the presence of Douglass School.

“I shall never forget the day when I first witnessed the pupils of the school taking the oath of allegiance. Several hundred little brown hands stretched forth to salute and as many voices with one accord pledged “allegiance to the flag and to the Republic for which it stands-—one nation indivisible with liberty and justice to all.” I know these children and their lot because I was once one of them. I knew them as a teacher and enjoyed their confidence.

“The scene, the setting, the expression epitomized to mind, more than anything else I know, the true spirit of America; it was the spirit which bridges the chasm between hope and reality. The early pioneers faced a wilderness and hoped for a civilization and it was: they later saw 13 colonies struggling each to itself. and hoped for these United States, and it came to be. Again they saw two great sections of our country divided and in conflict and they hoped for peace and a nation indivisible. This, too, came to pass. They hoped and those things are. Now we face a race problem on which statesmen have fallen and sound philosophers disagreed and these little children, its innocent victims in school and out dare to hope for its solution in liberty and justice to all. Because of the faith that abides in those our future citizens, I believe these things shall be.”